What’s the Time, Mr. Wolf?

]

]

And in the house’s warmth he could feel no comfort at all, not in the quiche he had made so carefully and chilled in the fridge, thinking he could feed her for once, not in the shower that he stood under until the hot water was gone, not in the bed with the good Belgian linen sheets and coverlet he’d ordered from one of Slim’s catalogues, not in the night, which he passed sleepless and shaking with rage.

He rose before dawn, and paced in the cottage until it felt too tight all around him, the air too stale to breathe. And then he was back in the car, on the highway, driving to nowhere in particular, just driving. He dipped down into Massachusetts, but the state depressed him with its gloomy skies and dead-looking trees and the sad snow-battered houses along the side of the highway, and he could never drive back to Boston and show himself so thoroughly diminished, so he drove for hours along the gray back roads until he found another highway and came back into New Hampshire through Manchester. He found himself in the center of this city he didn’t know or really ever care to know; he got out of his jeep and sat in a cold, denuded park. There were still ducks on the pond, silly creatures that could have flown somewhere warmer and kinder, to some retention pond in Louisiana or Florida full of rich weeds and delicious fish and a sun that came out as promised every day. But, no, they chose to stay for the crusts of moldy bread humans threw them, lazy beasts, and snow would fall on their suffering heads and they would die one night when the temperature dipped below freezing, in a huddle with the other dummy ducks, their hearts stopping one after the other until they were dead.

He was shuddering with cold when he got it in his mind to leave; the nights fell soon and fast so deep in winter now, and the twilight was already upon him. He hadn’t eaten anything in a very long time.

Chip walked into the center of the town, and the scent of food drew him into an empty restaurant where he lingered over a plate of Thai noodles. Across the street, there was a jeweller’s with its window decorated for Christmas, a splendid winter-wonderland town scene with laughing pink-cheeked statuettes and diamonds everywhere, earrings glinting off the eaves of the houses like icicles, a glimmering star brooch atop a Christmas tree, diamonds embedded in the tinfoil pond where more pink-cheeked statuettes were skating. He threw down his napkin and some cash and was across the street at the door of the jewelry store as if drawn there beyond his will.

The jeweller was closing up, but brightened when Chip came in. He was a small and vigorous man, something like an elf, and, when Chip lingered over a vitrine full of rings, he swiftly modelled the larger rings on his own small pale hands, citrine to turquoise to ruby to emerald. But Chip was not such a fool, he would not buy Pearl a ring, he knew that would scare her off for good. He moved on to the bracelets. Some were far too delicate for Pearl’s large wrist bones, others too gaudy for her tastes, but at last he saw a gold band with three perfect sapphire chips set off center, as though they made an ellipsis. He smiled, thinking of the symbolism. At the smile the little jeweller leapt, and nestled the bracelet in a froth of cotton, in a pretty pink box, and tied it with a silken bow and took Chip’s credit card and charged him a full month of mortgage payments for his condo, without Chip’s ever having fully agreed to buy the bracelet.

Chip was uneasy, but, when the jeweller handed the box solemnly to him, he felt that the man was putting hope itself into his hands. The gray cloud that had descended upon him lifted, and everything gleamed and shone all around him, the street itself made beautiful with this new feeling. Outside, the light from a liquor store dazzled his eyes, and he watched as if from far outside himself as he entered and bought a handle of bourbon, and would not let himself think of his sister’s disappointment, or of his own disappointment, only of the spicy burn and the warmth inside his stomach. He did not wait until he was in his jeep to open the bottle, but stopped on a quiet street and held the box with the bracelet between his legs and drank a few great gulps, and his head was pleasantly muffled when he turned the engine on.

Chip drove singing loudly through the dark, drinking from time to time, far too fast, feeling the thrill of the gift that sat like a tiny person in the passenger seat beside him. He thought of waiting until Christmas to give the bracelet to Pearl, but Christmas was still two weeks off, and his family was coming the week before, and, with them around, he would not see Pearl, and, well, since he had the courage, he might as well give the gift to Pearl now, get back in her graces. He checked the time. She would still be at the restaurant, he realized, so he drove up to her house, and parked at the town forest, and walked down to her house with the bourbon in one hand and the present in the other. He knew she kept her spare key under a rock in the shade garden by the mudroom door, and he let himself in. The dog barked, at first scared, then seeing it was him came out to meet him. He let the dog do its business in the yard, then fed both animals, taking off his boots and stowing them under the mudroom bench, and keeping the lights off.

How strange the house was in the night, he thought, looking around. It smelled the same, of dried herbs and Pearl, it was warm as ever, but, without the woman in it, the house was just a house. He went into her bathroom and sniffed her shampoos and conditioners, then came out and lay down on Pearl’s bed. But, just as he was drifting off to sleep, he startled himself awake; she would be seriously displeased to come home and find him already in her bed. He drank deeply, considering. The bottle felt light and he looked at it, marvelling how it was already so empty. At last, with a laugh, he understood what he needed to do, and he went into her closet and shut the door on himself, pushing aside her shoes. He would wait until she had showered and was nearly asleep to come out; this was when she was at her kindest, gentlest, most malleable, and he would climb in bed with her, kiss her, and she’d smile in her sleep and curl close to him.

The closet smelled like Pearl’s skin and lotion and shoe leather. It was stuffy but nice. Through the crack he could see a slice of light on the bedroom wall as her headlights came closer, then her engine shut off and her footsteps neared, and the kitchen door opened.

She greeted the dog and now there was a flood of light that fell from the kitchen area into the bedroom, but Pearl was still talking; she was, it seemed, offering the dog wine. How strange. No, something was not quite right here, this wasn’t the voice she normally used with the dog, and at last he understood with a sick lurch that she wasn’t alone. A deep male voice answered. Yes, it said, it would love some wine.

Chip could barely hear a thing then. His whole body was shaking, and his grip on the bottle was so tight he could hardly let it go when the glass began to rattle against the door. He breathed into his hands, suddenly sick with terror. The man he had seen with her was far larger than Chip was, and Chip was drunk, horribly drunk, oh, my God, how had he got here, how did he think this was a good idea. He was about to be murdered by that enormous man. He listened to Pearl feeding the dog, pouring the wine, saying she needed a shower, he heard the shower starting, Pearl singing to herself as she showered, and the warm damp steam reached him even where he was in the depths of her closet.

When she came out, she was naked. He saw her rosy flesh as she stood in the doorway of her bedroom saying, Put that down and come here. The man gave a laugh. Now Chip had to hear the wet and dreadful sounds they were making, the slip and grunt of people not himself having sex. He craned his neck but could see nothing but a hairy shoulder. Pearl came, the man came. There were whispers. Then Pearl began to breathe as she always breathed with a little snoring hitch in her nose, and Chip counted to himself, slowly.

At a thousand, he opened the closet door silently and moved through the lightless bedroom, through the kitchen, to the mudroom where he had forgotten the pink box on the bench when he took off his boots, it had been there all along, shining, perfect, fully visible if Pearl had been able to see it. Small mercies. He gathered the box and the boots up in his hands and carefully opened the mudroom door and closed it and ran in his wet cold socks into the forest far enough so that he could not be heard; then he put on his boots and went shaking back to the jeep. There was a wetness at his crotch, growing cold. He had pissed himself. He clutched the box in his arms until he was calm enough to start up the car and drive with headlights off past Pearl’s house. It wasn’t until he was home that he understood at last that he had left the bottle of bourbon and probably a stink of piss in Pearl’s closet.

He sat at his kitchen table, petrified in fear. When morning came, and he knew the general store would be opening for the old men who went to get their coffees and cider doughnuts and newspapers, he showered hurriedly and dressed and went down the mountain, and stood calling Elizabeth’s home number over and over until his sister was roused out of her deep sleep and angrily answered.

When he heard her voice, Chip started crying. He turned his back on the clerk, on the store with its buzzing lights and groaning refrigerators, the headlines grim about the snowstorm on the horizon. He put his head in the crook of his elbow and whispered, Libby?

Chippy? she said. What the hell. What’s going on?

But he couldn’t tell her. To tell her would be to see the last of his sister’s good opinion vanish forever. So he struggled to stop sobbing, to breathe. By the time he controlled himself, his sister had controlled herself, too.

Whatever it is, it’s really bad, huh, his sister said, coolly.

Yes, he said.

O.K., she said. Here’s the plan. I’ll be there as soon as I can. Listen, can you just hunker down? Can you just make it to the end of the day? I’ve got a deal I absolutely have to finish this morning, it’s like years and years of setting up, it absolutely must be nailed down today, but as soon as I’m done I’ll have them drive me a hundred miles an hour out to you. Don’t worry, Chippy. I’ll be there, I promise. Whatever this is, I can take care of it. O.K.?

O.K., he said. He knew she could not.

Don’t do anything stupid, she said. Go, like, take a hot shower, and go for a walk or something, all right? And then take another hot shower. Take a hot shower every two hours. You’ll be fine.

Right, sure, he said, and hung up, desolate.

He bought an egg sandwich and a coffee and came slowly up the mountain, but, when he saw the estate on its hill, his cottage shining in the blue morning against the forest, he knew he needed the mass of his family behind him, otherwise he would be too small against what he felt was coming. He drove the jeep into Bear’s garage, and went through the huge gloomy rooms of the big house until he was in Bear’s office, where, in the smell of pipe tobacco and cedar and dust, he felt safer.

Then he sat with a book in Bear’s wing chair. The drapes were pulled, but through the gap he could see down the dirt road for a good mile. He tried to read but could only imagine Pearl’s morning, her quick waking, washing, letting the dog out, making coffee, making breakfast for the man asleep in her bed. He thought he could feel her shock in his body when she opened the closet door and saw the bottle, the crumpled nest of shoes. When the smell of piss rose to her. He stood in agitation and rifled through his grandfather’s desk drawers until he found the secret stash of Bear’s favorite Scotch, and he drank it slowly to make his hands stop shaking.

It was almost midday when he saw the first of the caravan of trucks and cars coming up the dirt road, and he steeled himself and moved to the other side of the house, to Slim’s blue-gray dressing room, where through her sheer curtains he could watch his cottage. The trucks pulled in and parked around it. Dark-haired men got out, stout and thin, a half-dozen or so, and conferred in a knot. These must be Pearl’s family, here to threaten him, and he felt a sinking sadness that he had never got to meet them, or else they would have known he was a good guy, a gentleman, that he would never have hurt her. One of them went up to the door and knocked and, with no answer, swung the door open and went inside. Then some of the younger men entered, and Chip’s great-great-grandmother’s books came flying out the door, their brittle leaves spilling, and the few clothes and shoes he had were dumped in a drift, and one of the older men went to the woodshed and came back with the axe, which he embedded in the door.

Southern California Seasonal Produce Guide

By now you’ve heard it so often it’s become a cliché – to cook best, you must cook seasonally. But how do you really know what’s in season? When you go to the supermarket, they seem to have the same fruits and vegetables all through the year.

The Los Angeles Times’ Southern California Seasonal Produce Guide, will keep you up to date with what’s at its best no matter what time of year.

Not only will you learn which fruits and vegetables you should be looking for, you’ll also find out how to choose the best, how to take care of them once you’ve bought them, simple preparation tips and a whole bunch of recipes from among the nearly 6,000 in our Cooking section.

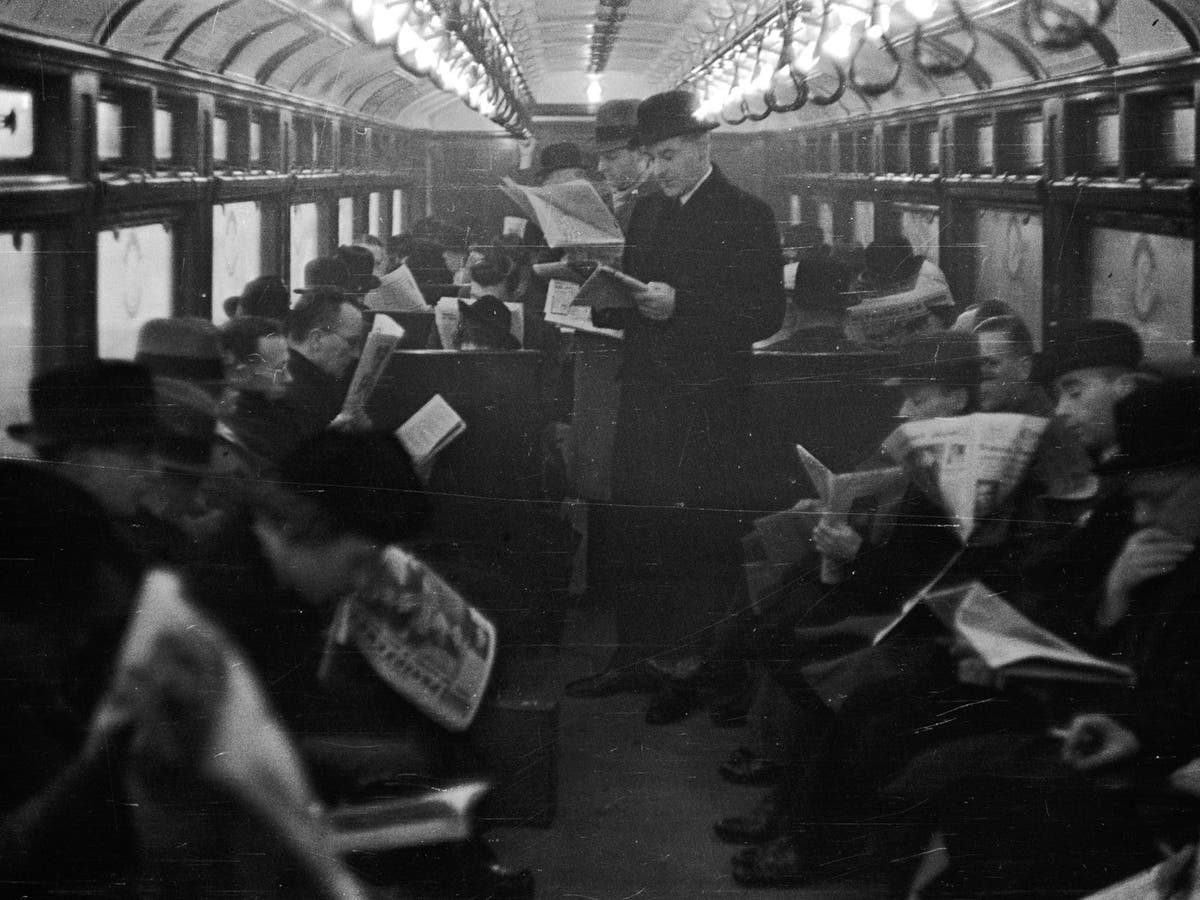

When taking the train was a sign of prosperity

]

]

Last week, the nation’s notional “commuters” made their annual appearance in the press. They did their usual party piece, expressing fury at the “10th year of above-inflation fare increases” and “4.2 per cent average increase in season ticket prices”.

The Transport minister Norman Baker suggested that rush-hour travel is a “premium product” and people should expect to pay more for it. If we could look into Mr Baker’s mind, I suspect we would see an image of a commuter that is 40 years out of date: a prosperous, pin-striped man, umbrella and newspaper tightly furled, who slams the door of his slam-door train with military briskness. In those days, the commuter was the prosperous counterpart to the factory employee who walked to work. But there are no factories left. Today, most of us are commuters.

Stephen Joseph, the executive director of the Campaign for Better Transport, says that British commuting is at an all-time high. “Immediately postwar, we had the New Towns and diffuse development. But the pattern changed in the Eighties and Nineties, and today we have strong city centres accommodating the offices of a service economy. London is growing fast, but we’re also seeing big increases in commuting into Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds.”

Back in the early Eighties, one Jimmy Savile asserted that “this is the age of the train”. But in fact this is the age of the train, with rail use at its highest since the Twenties – when there were few cars about – and it is continuing to rise even in a time of recession. And the biggest increase has been in business travel. There are many factors at work: the train operators will point to their customer care and marketing initiatives; there is road congestion and congestion charging; and young men, in particular, no longer buy cars as a reflex action on leaving university. They can’t afford them. Also, you rarely come across “the company car”, a type of vehicle now taxed at a level I would call appropriate.

The teleworking revolution that was supposed to transform our lives never really happened. Yes, people work at home, but this is in addition to working in the office and on the train. There is also the phenomenon of “presenteeism”: in these turbulent economic times, people want to be able to answer to their name when the register is called.

In light of this, I think commuters deserve a more prominent role than they are currently accorded. The male commuter used to be a stock figure with his bowler hat, newspaper lowered only when some faux pas was committed in the compartment. In a Two Ronnies sketch of 1980, Ronnie Barker played a commuter trying to do the Mephistopheles crossword in the FT. Alongside him in the compartment, Ronnie Corbett attempts The Sun’s Junior Coffee Time easy clues crossword. Barker lowers his paper and raises an eyebrow, as Corbett reads out the clue: “They peck holes in your milk bottle tops… something- something-T-S”, before Corbett triumphantly pronounces, “Bats!” Barker can’t help but correct him, remarking that Sun readers should know the answer.

The commuter represented regularity and conformity, usually for satirical purposes. In the 1961 film The Rebel, Tony Hancock plays a man who, on boarding his morning train, sighs: “Journey number 6,833.” He yearns to be an artist of “the Impressionist school”. Within this genre, the commuting life went with a job that presented an existential crisis, and Hancock works for the faceless-sounding United International Transatlantic Consolidated Amalgamation Ltd. In The Good Life (1975), Tom Good is so depressed by commuting to a firm that makes plastic toys for breakfast cereal packets that he resigns and attempts to become self-sufficient in Surbiton. In The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin (1976), Perrin is driven to mid-life crisis by commuting from a south London suburb to Sunshine Desserts. Every morning he is late, and presents excuses ranging from the just-about plausible (“Overheated axle at Berrylands”) to the not so plausible (“Badger ate a junction box at New Malden” or “Escaped puma, Chessington North”).

One of the last pieces of commuter commentary was a book in 1984 written under the pseudonym Tiresias called Notes from Overground. With exquisite melancholia, it recorded a 20-year daily commute from Oxford to London: “When the train passes any kind of sporting activity … invariably nothing is happening. The bowler is always about to bowl, the referee about to restart play, the archer poised to shoot. Nothing takes place before our profane gaze. At our uncouth advent, the initiates freeze in a tableau vivant, waiting for us to pass before they resume celebration of the mysteries. This… phenomenon underlines the lack of rapport between our unnatural train existence and normal life outside.” Is the commuting life really unnatural? We ought, at least, to ask the question.

Next Wednesday, we will be encouraged to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the London Underground, whose fares also rose last week. The first line was the Metropolitan. Its chief begetter, the lawyer and social reformer Charles Pearson, believed that in commuting – he called it “oscillating” – lay the answer to the misery of the London poor, who were packed into the rookeries of what is now considered desirable central London. He had noted the way they enjoyed Sunday excursions to the country, often keeping a flower in a broken teapot on the mantelpiece as symbolic of a better life.

The interwar expansion of the Underground was an attempt to promote growth, but the net result was to make London a commuter city. As Mr Aked observes in Arnold Bennett’s novel A Man from the North: “Why, the suburbs are London!” Usually, the developers followed the Underground lines. Only in the case of the Metropolitan did the railway company itself build the houses. In the Twenties, the Met created Metroland in north-west London within a “verdant realm” of “gentle, flower-decked downs”. So arose Neasden and other dormitories. Metroland destroyed the countryside that was its selling point.

It has long been commonplace to sneer at “suburban” values, even though most of us live there. Ever since the Eighties, the aspiration of the fashionable has been to live centrally, while the synonym for black youth culture, to which most of white youth aspires, is “urban”.

Commuters have become invisible by virtue of their ubiquity. And there is another consideration. Under the intense pressure of a competitive, materialistic and globalised world, we can’t afford the luxury of questioning our economic roles. The problem today is how to get into the rat race, not how to get out of it. The fact is that we all work for United International Transatlantic Consolidated Amalgamation Ltd, and there is little more to be said on the matter.

Andrew Martin’s book, ‘Underground Overground: a Passenger’s History of the Tube’ is published in paperback on Thursday