This debacle has exposed Joe Biden as a failed president

]

]

Joe Biden has no interest in your facts. Those are from four or five days ago. Or, actually, two.

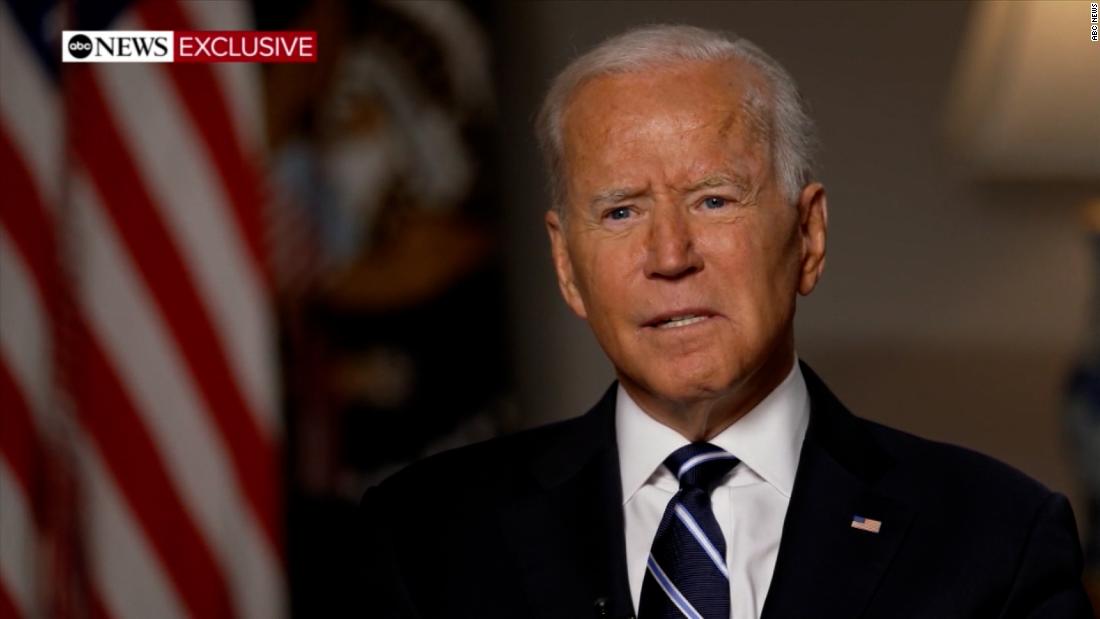

In his contentious interview with ABC’s George Stephanopoulos — his sentences jumbled together, alternately rambling and insisting with vociferous certainty things that were not true — Biden came across as an image of incompetent frailty.

For a man who promised a restoration of American unity after years of intense political conflict, Biden has achieved this goal: Everyone now thinks he failed. No matter your feelings about Afghanistan — whether you thought we should get out now, or 10 years ago, or never — Americans all agree this exit is a debacle, an embarrassment of logistical planning that has left our fellow citizens and our allies in the lurch.

Yet Biden will brook no objections to his approach. Stephanopoulos, ever the dutiful Democratic coffee boy, gave him one softball after another to cast blame or meander toward an excuse. Biden didn’t take it. Instead, he deployed his cantankerous Scranton Joe personality familiar to many of us who saw him in his Senate days — an old man raising his voice and insisting he knows best, despite all evidence to the contrary.

Joe Biden is derelict in his duty. His State Department failed to prepare adequately to get Americans and our allied Afghans out of the country in time. His Department of Defense made the decisions that left our resources and materiel to be used by the Taliban. His intelligence units were the ones he now claims — despite evidence to the contrary — never warned that the Afghan government could fall so fast.

This was a failure of many institutions of American government. But above all, it was a failure of the Commander in Chief.

A man carries a bloodied child on the street as Taliban fighters punish thousands of Afghans waiting outside of the Kabul Airport in Afghanistan on August 17, 2021. MARCUS YAM/LOS ANGELES TIMES/Shutterstock

The media depicted Joe Biden as an American comeback — that the arc of history, having been momentarily disrupted by a populist brigand in Donald Trump, would now return to its proper state.

But a problem has emerged in this narrative, and that problem is Joe Biden. He is not the leader that was promised. His version of normalcy — chaos at the southern border, inflation hitting every household, a return to mandates and lockdowns, massive debt spending, and an anti-American education system run amok — hurts your average working American. And every smart Democratic operative can see the tidal wave heading their way because of it.

There were many in the Republican coalition who objected to Trump’s reform of the foreign policy as a more isolationist, America First philosophy. But at its base definition, America First is a pragmatic policy designed to inspire trust from our friends and fear in our enemies.

Biden’s failed Afghanistan exit inspires nothing of the sort. It manages to make America look both faithless and stupid. And the whole world knows it.

Fact-checking Biden’s ABC interview on Afghanistan

]

]

Washington (CNN) President Joe Biden sat down with ABC News anchor George Stephanopoulos on Wednesday for an interview that focused on the US withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Biden made some inaccurate claims in the interview – which was released in part on Wednesday and in full on Thursday – plus some other claims that, at least, could have used some more context.

US troops in Syria

Stephanopoulos asked about a possible al Qaeda terror threat to the US as a result of the withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Biden said, “Al Qaeda, ISIS, they metastasize.” He then argued that the US faces a “significantly greater” terror threat from Syria and East Africa than it does from Afghanistan.

Biden continued with regard to Afghanistan: “And we have maintained the ability to have an over-the-horizon capability to take them out. We’re – we don’t have military in Syria to make sure that we’re going to be protected…”

Facts First: Depending on Biden’s meaning, his remark about Syria is either plainly incorrect or, at least, missing important context. There are : Depending on Biden’s meaning, his remark about Syria is either plainly incorrect or, at least, missing important context. There are roughly 900 US troops in Syria, focused on supporting Kurdish forces in the battle against the Islamic State terror group also known as ISIS.

An administration official who spoke on condition of anonymity told CNN on Thursday that Biden “was speaking about the al Qaeda presence in northwest Syria, which remains a threat to the United States and is being addressed without American troops on the ground. There are a small number of US and coalition forces on the ground in eastern Syria in areas that had been the ISIS caliphate.”

Regardless of Biden’s intentions, he did not make clear to ABC viewers that he was talking about a specific part of Syria rather than Syria as a whole, or that he was talking about al Qaeda in particular rather than ISIS as well.

When the dramatic plane images were taken

When Stephanopoulos began to ask Biden about dramatic images the public has seen this week – of hundreds of Afghans packed into a US military plane and of Afghans falling off the outside of a US military plane as it was in the air – Biden, who was trying to emphasize that the situation had since improved, interjected, “That was four days ago, five days ago.”

After Stephanopoulos continued by asking what Biden thought when he saw the images, Biden responded, “What I thought was, we have to gain control of this. We have to move this more quickly. We have to move in a way in which we can take control of that airport. And we did.”

Facts First: Unless Biden was talking about images the public hasn’t seen, his timeline was off. In reality, the images that were publicized around the world were taken less than 72 hours, or three full days, before Biden’s remarks. “Five days ago” is clearly wrong for both of the images Stephanopoulos described. “Four days ago” is wrong about at least one of the images – and wrong about both unless you are counting days quite creatively.

Here’s a rough timeline.

Biden recorded the interview with Stephanopoulos around 2 p.m. ET on Wednesday, according to an ABC official. Videos of people falling from a US plane were tweeted by Afghan journalists early Monday morning ET; while we don’t have the exact time of the tragic incident, Afghanistan’s Aśvaka news agency, which posted one of the first videos at 4:11 a.m. ET on Monday, told CNN in a Twitter message on Wednesday that its tweet went up very shortly after the footage was taken, minutes later rather than hours. So we can be confident the incident occurred less than three days before Biden’s interview, not four days or five days.

Meanwhile, a US military flight crammed with hundreds of fleeing Afghans – of which the publication Defense One published a dramatic photo on Monday – took off from Kabul on Sunday Eastern Time, in the afternoon or early evening. (Defense One said “late Sunday.”) Perhaps someone out there counts late Sunday as “four days ago” in relation to early Wednesday afternoon, but that’s a stretch; the flight took off less than 72 hours before Biden made the claim.

Biden’s position on “nation-building”

Biden said of the US presence in Afghanistan: “We went there for two reasons, George. Two reasons. One, to get bin Laden, and two, to wipe out as best we could, and we did, the al Qaeda in Afghanistan. We did it. Then what happened? Began to morph into the notion that, instead of having a counterterrorism capability to have small forces there in – or in the region – to be able to take on al Qaeda if it tried to reconstitute, we decided to engage in nation-building. In nation-building. That never made any sense to me.”

Facts First: It’s inaccurate for Biden to claim that nation-building “never” made sense to him – given that he explicitly and repeatedly advocated nation-building in the early years of the war in Afghanistan. Until at least 2004, Biden called for nation-building both in Afghanistan and in the world more broadly.

We’re not criticizing Biden for holding a different view today as president than he did more than 15 years ago as a US senator for Delaware; he’s entitled to change his mind over time, and his shift on Afghanistan occurred even before he became vice president in 2009 . But given his public remarks in the early 2000s, it’s incorrect for him to suggest he “never” supported nation-building in Afghanistan.

In October 2001, after the Bush administration began bombing Afghanistan, Biden was asked on CBS: “Should we be in the business of nation-building?” He responded, “Absolutely, along with the rest of the world.”

Different people define “nation-building” differently. Very generally, the term tends to be used by Washington lawmakers to describe efforts to help build countries like Afghanistan and Iraq into functional states with effective state institutions, as opposed to narrower military-focused efforts to simply target terrorists and fight battles.

In a February 2003 statement at a meeting of the Senate foreign relations committee, Biden said that, while visiting Kabul the year prior, he was repeatedly asked, “Will America help to rebuild Afghanistan, or will we just declare victory and go home?” He said these Afghans were worried about the “long-term commitment” of the US to Afghanistan given that the US had “lost interest” in the country after helping to drive out the Soviet Union in 1989.

“Nation-building was slow, frustrating, and, above all, expensive. So, as my hosts in Kabul reminded me, we quickly left the Afghans to fend for themselves,” he said. “In some parts of this [Bush] administration, ’nation-building’ is a dirty phrase. But the alternative to nation-building is chaos – a chaos that churns out bloodthirsty warlords, drug traffickers, and terrorists. We’ve seen it happen in Afghanistan before, and we’re watching it happen in Afghanistan today.”

At another committee meeting later that month, Biden repeated his warming that “the alternative to nation-building is chaos.”

Then, according to a report on the website of Princeton University, Biden issued a general endorsement of nation-building in a February 2004 speech at the school: “We also need a new attitude, an attitude that suggests that projecting power should not occur in an elective war absent a commitment to staying power. Don’t project the power unless you’re prepared to have staying power. Nation-building – that ‘four-letter word’ in this administration up to now – is an absolute prerequisite for the 21st century.”

And in a September 2004 op-ed in the Wall Street Journal , Biden wrote, “We also have to take seriously nation-building. This administration came to office disdaining the concept, only to be confronted with the two biggest nation-building challenges since World War II. Thus far, it merits a failing grade in both Afghanistan and Iraq.” Biden wrote that a Democratic administration “would empower experts to plan post-conflict reconstruction ahead of time, not on the fly.”

The number of Afghan troops

Biden said he didn’t think anybody anticipated “that somehow the 300,000 troops we had trained and equipped was going to just collapse, they were going to give up.”

Facts First: Biden didn’t invent this “300,000” figure; it has been used for years by the : Biden didn’t invent this “300,000” figure; it has been used for years by the US military think tanks and various media outlets. But independent experts say that, in reality, the Afghan military had far fewer than 300,000 troops before its collapse.

A bit later in the interview with ABC, Biden amended the figure to “up to 300,000,” which is at least somewhat more accurate. However, there is good reason to doubt the 300,000 figure even as an upper-bound estimate.

First of all, the 300,000 figure includes more than 118,000 listed employees of the Afghan police. Anthony Cordesman , the Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank and a former federal official, said it is “fundamentally dishonest” to “count police as troops,” since, he said, they were not sufficiently trained or equipped to fight Taliban forces.

In addition, the US government’s watchdog for the Afghanistan war repeatedly warned that there were multiple reasons to doubt official figures about the Afghan security forces.

The figures were consistently marred by the problem of so-called “ghost” fighters: no-show soldiers and police officers who were listed on the employee rolls only so corrupt people could collect their salaries. Also, the forces were plagued by extraordinarily high turnover, about a quarter of the entire employee roster in a given year.

Jonathan Schroden, who has studied the Afghan forces as director of the Countering Threats and Challenges Program at CNA, a federally funded research and analysis organization in Virginia, estimated to CNN this week that the true number for the pre-collapse Afghan military was “likely” in the range of 150,000 to 200,000 people.

Allies embraced Biden. Did Kabul lay bare “great illusion”?

]

]

FILE - In this June 14, 2021 file photo, President Joe Biden and NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg speak while visiting a memorial to the September 11 terrorist attacks at NATO headquarters in Brussels. When U.S. President Joe Biden took office early this year, Western allies were falling over themselves to welcome and praise him and hail a new era in trans-Atlantic cooperation. The collapse of Kabul certainly put a stop to that. Even some of his biggest fans are now churning out criticism. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky, File)

FILE - In this June 14, 2021 file photo, President Joe Biden and NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg speak while visiting a memorial to the September 11 terrorist attacks at NATO headquarters in Brussels. When U.S. President Joe Biden took office early this year, Western allies were falling over themselves to welcome and praise him and hail a new era in trans-Atlantic cooperation. The collapse of Kabul certainly put a stop to that. Even some of his biggest fans are now churning out criticism. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky, File)

BRUSSELS (AP) — Well before U.S. President Joe Biden took office early this year, the European Union’s foreign policy chief sang his praises and hailed a new era in cooperation. So did almost all of Washington’s Western allies.

The EU’s Josep Borrell was glad to see the end of the Trump era, with its America First, and sometimes America Only policy, enthralled by Biden’s assertion that he would “lead, not merely by the example of our power, but by the power of our example.”

Sunday’s collapse of Kabul, triggered by Biden’s decision to get out of Afghanistan and a U.S. military unable to contain the chaos since, certainly put a stop to that. Even some of his biggest fans are now churning out criticism.

Borrell was among them, this time aghast at Biden’s contention that “our mission in Afghanistan was never supposed to have been nation-building,” coming in the wake of Western efforts over much of the past two decades to sow the seeds of the rule of law and assure protection for women and minorities.

ADVERTISEMENT

“State-building was not the purpose? Well, this is arguable,” a dejected Borrell said of Biden’s stance, which has come under criticism in much of Europe.

And for many Europeans steeped in soft power diplomacy to export Western democratic values, Biden’s assertion that, “our only vital national interest in Afghanistan remains today what it has always been: preventing a terrorist attack on American homeland,” could have come from a Trump speech.

EU Council President Charles Michel underscored the different stances when he said in a tweet Thursday that the “rights of Afghanis, notably women & girls, will remain our key concern: all EU instruments to support them should be used.”

French Parliamentarian Nathalie Loiseau, a former Europe minister for President Emmanuel Macron, put the unexpected EU-Biden disconnect more bluntly: “We lived a little bit the great illusion,” she said. “We thought America was back, while in fact, America withdraws.”

It was no better in Germany, where a leading member of German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s center-right Union bloc, Bavaria Gov. Markus Soeder, called on Washington to provide funding and shelter to those fleeing Afghanistan, since “the United States of America bear the main responsibility for the current situation.”

Even in the United Kingdom, which has always prided itself on a its “special relationship” with Washington and now, more than ever, needs U.S. goodwill to overcome the impact of leaving the EU, barbs were coming from all angles.

Former British Army chief Richard Dannatt said, “the manner and timing of the Afghan collapse is the direct result of President Biden’s decision to withdraw all U.S. forces from Afghanistan by the 20th anniversary of 9/11.”

ADVERTISEMENT

“At a stroke, he has undermined the patient and painstaking work of the last five, 10, 15 years to build up governance in Afghanistan, develop its economy, transform its civil society and build up its security forces,” Dannatt said Wednesday in Parliament.

“The people had a glimpse of a better life — but that has been torn away.”

Biden has pointed to the Trump administration deal negotiated with the Taliban 18 months earlier in Doha, Qatar, which he says bound him to withdraw U.S. troops, as setting the stage for the chaos now engulfing the country.

Still, Biden putting much of the blame on Afghan forces for not protecting their nation has not gone down well with Western allies, either.

Conservative Parliament member Tom Tugendhat, who fought in Afghanistan, was one of several British lawmakers taking offense.

“To see their commander-in-chief call into question the courage of men I fought with, to claim that they ran, is shameful,” Tugendhat said.

Chris Bryant, from the opposition Labour Party, called Biden’s remarks about Afghan soldiers, “some of the most shameful comments ever from an American president.”

In Prague this week, Czech president Milos Zeman said that, “by withdrawing from Afghanistan, the Americans have lost their status of global leader.”

But despite all the criticism, there is no doing without the United States on the global stage. America remains vital to the Western allies in a series of other issues, in particular taking action against global warming.

After climate change disasters across much of the globe this year, the EU will be counting heavily on Biden to stand shoulder-to- shoulder in taking effective measures at the November COP26 global conference in Glasgow, Scotland, to speed up action to counter global warming.

Europe and Washington also have enough trade disagreements to settle to realize that despite the debacle of Afghanistan, there is much more that unites than divides them. A need for American power and help remains, even in Afghanistan.

Before Friday’s meeting of NATO foreign ministers, some Alliance nations have acknowledged they will be pleading to Washington to stay even longer in Afghanistan than it will take to bring all U.S. citizens home, wanting to make sure their people get out too.

“We and a number of other countries are going to the Americans to say: ‘Stay as long as possible, possibly longer than necessary,’” Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs Sigrid Kaag said.

Associated Press writers Mike Corder in The Hague, Netherlands; Sylvia Hui in London; Karel Janicek in Prague and Colleen Barry in Milan contributed.