The Statesman

]

]

With global economies and communities still reeling under the crippling weight of the Covid-19 pandemic that started from China, the scale of the 100th anniversary celebration of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was almost mocking in its temerity. While propaganda is an irreplaceable and invaluable tool in the hands of authoritarian regimes to ‘control’ the essential narrative, no example comes as close to the success of propaganda as that of Xi Jinping’s China.

Symbolism of confidence, assertion and future were at the heart of the highly orchestrated display of purpose as Xi spoke of ‘Making China Great again’, in the backdrop of impressive fly-pasts and marches, 56 guns firing 100 times and release of 100,000 eco-friendly balloons and doves. A fiery, defiant and intimidatory show of steely resolve was omnipresent.

Behind the puerile display of self-congratulatory tonality for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) for creating the ‘great wall of steel’, the foremost thought that haunted the CCP top brass was clearly visible ~ fears of a popular uprising leading to regime change, and its accompanying insecurities. Xi Jinping’s words echoed the desperation to equate the perpetuity of CCP to China’s prosperity, “China’s success hinges on the Party…. without the Communist Party of China, there would be no new China and no national rejuvenation”.

The continuum of China’s manifest destiny was carefully stitched weaving the past, present and the inevitable glories that awaited ~ towards the same, the ever-evolving admixture of Chinese nationalism, coercion, control, and purge was ubiquitous.

There was no hesitation or awkwardness imagined to curate the national sentiment, as the revered and ancient Chinese texts sanctify the leader’s, ‘Mandate of Heaven’. So, besides hailing its first centenary goal of building a ‘moderately prosperous society’ for all, the focus shifted towards drumming nativist passions by insisting that it would not get ‘bullied, oppressed or subjugated’ and that it would not accept ‘sanctimonious preaching’ from anyone. The wary instinct of protectionism was palpable, and all-pervasive.

To the credit of the Chinese Communist Part, unlike the more intransigent and doctrinaire forms of residual communism in the world, it has managed to evolve and incorporate the topical aspirations of societies, whilst still retaining the levers of ‘control’ and denial. The tokenism of concluding the ceremony with ‘The Internationale’ or invoking the foundational legacy of Mao Zedong, with images of him looking into the skies in a theatrical fashion (despite having the blood of over 40 million Chinese on his hands, with programmes like Cultural Revolution and Great Leap famine, notwithstanding), Xi’s phraseology and vision reflects the burning desires of ‘today’s generation’, and therefore his supreme ability to ensure ‘connect’ with the masses, who no longer suffer the wounds of the past. His hybrid model of governance may even look contradictory ~ but China is determined to showcase a muscular, integrated, and efficacious face of ‘State Capitalism’.

In times like the pandemic, Xi Jinping’s ability to muster resources, action and focus as a one-party state is unmatched, leading him to mock US and other democracies for their ostensible failures. Yet the celebrations with the carefully vetted crowds, picture-perfect images of cultural performances, weaponry of unprecedented stealth and reach, could barely mask the nervous tension that besets the Chinese undercurrents.

Cues of Chinese popular passions were resonating in Xi’s speech, both in what he did mention, and in what he did not. While the Chinese PLA (People’s Liberation Army) is a unique phenomenon as the military of a political party, it did posthumously honour a PLA soldier, Chen Hongjun, who was amongst the several who died in the clash with Indian forces, at Galwan, last year. Even then, the delayed acceptance of its own casualties after the initial denials, was a typical attempt of ‘controlling’ the narrative ~ now, this soldier was one of the 29, awarded the ‘July 1 medal’ for his ostensible efforts to, ‘stay true to the original aspiration and dedicate everything, even the precious life, to the cause of the party and people’.

Other than this event preceding the main celebrations, there was no specific mention or allusion to India, despite the fractured reality. This signifies a far less-than-glorious Chinese performance during the violent standoff, as indeed, suggestions of an amoral, expansionist and intimidatory image that could militate against the one Xi was desperately cultivating. This also signified the limited traction in ‘enemyfying’ India, vis-à-vis other options available.

The core of Xi’s international focus and wrath revolved around the ‘US and Western organisations’, confirming his principal adversarial concerns and outlook. The gentle cooption of Russian history and import of Communism to China was telling in its strategic outreach and dynamics. On the simmering tensions in Hongkong and Macau, Xi confirmed, ‘We will stay true to the letter and spirit of the principle of One Country, Two Systems’, and on the most contentious issue of Taiwan, he reiterated, ‘Resolving the Taiwan question and realizing China’s complete reunification is a historic mission and an unshakable commitment of the Communist Party of China’, knowing fully well the reaction it would elicit, domestically and internationally.

The deliberate play of words to cherry pick some, whilst not intending to carry forward the same in letter and spirit was visible, when he posited the hybrid Chinese model with the assurance to continuously work to ‘develop whole-process people’s democracy’ ~ this when the illiberalities, intolerances and impulses of ‘control’ have regressed to the levels of earlier decades.

Obviously, there was no mention of the elephant in the room as far as the international community was concerned, that is the incarcerated Uyghur minorities, as that expectedly did not suit the projected storyline.

Reaffirmation of its Belt and Road Initiative (without addressing the growing international concerns on its ‘debt-trap’ inevitabilities) was undertaken, as was the ponderous promise to continue, ‘building of a human community with a shared future’!

In all Xi Jinping stuck to the expected script with shades of grandstanding, grandiloquence, and barely veiled intimidations, which were not lost on anyone. The neologism of an emerging ‘Chinese Century’ with the usual filters to hide blemishes, blunders and insecurities marked the day ~ more of the same is to be expected going forward from a no-longer-shy China.

China’s path to modernization has, for centuries, gone through my hometown

]

]

In 1957, Yang and Tsung-Dao Lee, a fellow Chinese graduate of the University of Chicago, won the Nobel Prize for proposing that when some elementary particles decay, they do so in a way that distinguishes left from right. They were the first Chinese laureates. Speaking at the Nobel banquet, Yang noted that the prize had first been awarded in 1901, the same year as the Boxer Protocol. “As I stand here today and tell you about these, I am heavy with an awareness of the fact that I am in more than one sense a product of both the Chinese and Western cultures, in harmony and in conflict,” he said.

Yang became a US citizen in 1964 and moved to Stony Brook University on Long Island in 1966 as the founding director of its Institute for Theoretical Physics, which was later named after him. As the relationship between the US and China began to thaw, Yang visited his homeland in 1971—his first trip in a quarter of a century. A lot had changed. His father’s health was failing. The Cultural Revolution was raging, and both Western science and Chinese tradition had been deemed heresy. Many of Yang’s former colleagues, including Huang and Deng, were persecuted and forced to perform hard labor. The Nobel laureate, on the other hand, was received like a foreign dignitary. He met with officials at the highest levels of the Chinese government and advocated for the importance of basic research.

In the years that followed, Yang visited China regularly. At first, his trips drew attention from the FBI, which saw exchanges with Chinese scientists as suspect. But by the late 1970s, hostilities had waned. Mao Zedong was dead. The Cultural Revolution was over. Beijing adopted reforms and opening-up policies. Chinese students could go abroad for study. Yang helped raise funding for Chinese scholars to come to the US and for international experts to travel to conferences in China, where he also helped establish new research centers. When Deng Jiaxian died in 1986, Yang wrote an emotional eulogy for his friend, who had devoted his life to China’s nuclear defense. It concluded with a song from 1906, one of his father’s favorites: “[T]he sons of China, they hold the sky aloft with a single hand … The crimson never fades from their blood spilled in the sand.”

Yang (seated, left) with fellow Nobel Prize winners (clockwise from left) Val Fitch, James Cronin, Samuel C.C. Ting, and Isidor Isaac Rabi ENERGY.GOV, PUBLIC DOMAIN, VIA WIKIMEDIA

Yang retired from Stony Brook in 1999 and moved back to China a few years later to teach freshman physics at Tsinghua. In 2015, he renounced his US citizenship and became a citizen of the People’s Republic of China. In an essay remembering his father, Yang recounted his earlier decision to emigrate. He wrote, “I know that until his final days, in a corner of his heart, my father never forgave me for abandoning my homeland.”

In 2007, when he was 85 years old, Yang stopped by our hometown on an autumn day and gave a talk at my university. My roommates and I waited outside the venue hours in advance, earning precious seats in the packed auditorium. He took the stage to thunderous applause and delivered a presentation in English about his Nobel-winning work. I was a little perplexed by his choice of language. One of my roommates muttered, wondering whether Yang was too good to speak in his mother tongue. We listened attentively nevertheless, grateful to be in the same room as the great scientist.

A college junior and physics major, I was preparing to apply to graduate school in the US. I’d been raised with the notion that the best of China would leave China. Two years after hearing Yang in person, I too enrolled at the University of Chicago. I received my PhD in 2015 and stayed in the US for postdoctoral research.

Months before I bid farewell to my homeland, the central government launched its flagship overseas recruitment program, the Thousand Talents Plan, encouraging scientists and tech entrepreneurs to move to China with the promise of generous personal compensation and robust research funding. In the decade since, scores of similar programs have sprung up. Some, like Thousand Talents, are supported by the central government. Others are financed by local municipalities.

Beijing’s aggressive pursuit of foreign-trained talent is an indicator of the country’s new wealth and technological ambition. Though most of these programs are not exclusive to people of Chinese origin, the promotional materials routinely appeal to sentiments of national belonging, calling on the Chinese diaspora to come home. Bold red Chinese characters headlined the web page for the Thousand Talents Plan: “The motherland needs you. The motherland welcomes you. The motherland places her hope in you.”

These days, though, the website isn’t accessible. Since 2020, mentions of the Thousand Talents Plan have largely disappeared from the Chinese internet. Though the program continues, its name is censored on search engines and forbidden in official documents in China. Since the final years of the Obama administration, the Chinese government’s overseas recruitment has come under intensifying scrutiny from US law enforcement. In 2018, the Justice Department started a China Initiative intended to combat economic espionage, with a focus on academic exchange between the two countries. The US government has also placed various restrictions on Chinese students, shortening their visas and denying access to facilities in disciplines deemed “sensitive.”

My mother is afraid that the borders between the US and China will be closed again as they were during the pandemic, shut down by forces just as invisible as a virus and even more deadly.

There are real problems of illicit behavior in Chinese talent programs. Earlier this year, a chemist associated with Thousand Talents was convicted in Tennessee of stealing trade secrets for BPA-free beverage can liners. A hospital researcher in Ohio pled guilty to stealing designs for exosome isolation used in medical diagnosis. Some US-based scientists failed to disclose additional income from China in federal grant proposals or on tax returns. All these are cases of individual greed or negligence. Yet the FBI considers them part of a “China threat” that demands a “whole-of-society” response.

The Biden administration is reportedly considering changes to the China Initiative, which many science associations and civil rights groups have criticized as “racial profiling.” But no official announcements have been made. New cases have opened under Biden; restrictions on Chinese students remain in effect.

Seen from China, the sanctions, prosecutions, and export controls imposed by the US look like continuations of foreign “bullying.” What has changed in the past 120 years is China’s status. It is now not a crumbling empire but a rising superpower. Policymakers in both countries use similar techno-nationalistic language to describe science as a tool of national greatness and scientists as strategic assets in geopolitics. Both governments are pursuing military use of technologies like quantum computing and artificial intelligence.

“We do not seek conflict, but we welcome stiff competition,” National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said at the Alaska summit. Yang Jiechi responded by arguing that past confrontations between the two countries had only damaged the US, while China pulled through.

Much of the Chinese public relishes the prospect of competing against the US. Take a popular saying of Mao’s: “Those who fall behind will get beaten up!” The expression originated from a speech by Joseph Stalin, who stressed the importance of industrialization for the Soviet Union. For the Chinese public, largely unaware of its origins, it evokes the recent past, when a weak China was plundered by foreigners. When I was little, my mother often repeated the expression at home, distilling a century of national humiliation into a personal motivation for excellence. It was only later, in adulthood, that I began to question the underlying logic: Is a competition between nations meaningful? By what metric, and to what end?

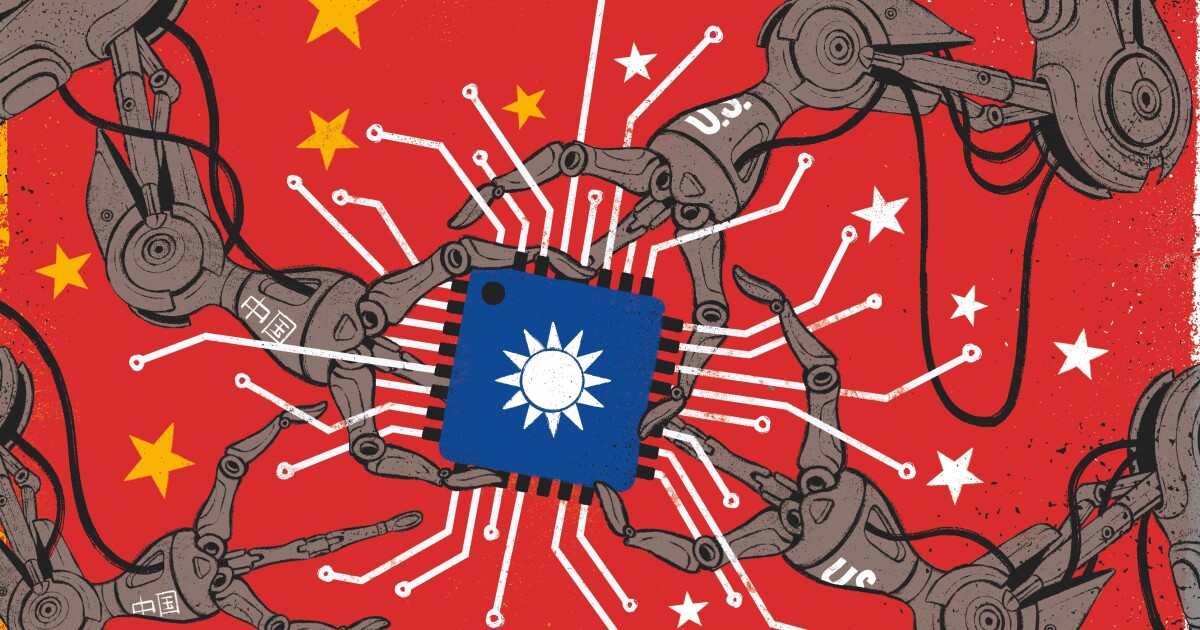

The most important company you’ve never heard of is being dragged into the U.S.-China rivalry

]

]

It’s been called Taiwan’s Silicon Shield, and without it much of modern life would cease.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., or TSMC, makes more than half the world’s contracted semiconductor chips and lies at the center of the technology supply chain, churning out circuitry found in iPhones, Amazon cloud computers, graphics processors that power popular video games and even military drones and fighter jets like Lockheed Martin’s F-35.

But TSMC is confronting problems it had never anticipated when a Taiwanese American engineer, who spent 25 years at Texas Instruments and is revered here like a hometown Bill Gates, founded it in the late 1980s. The company has been drawn into an increasingly bitter — and at times dangerous — rivalry between the U.S. and China that is forcing nations and corporations to choose sides in an era that is redefining the global order.

The competition for technology and geopolitical sway between the two superpowers is a threat to TSMC and this self-ruled island democracy of 24 million, which Beijing considers part of China and has hinted it might invade to reclaim. The company has encountered cyberattackers and had its engineers wooed away in a strategy by China to accelerate its own technological growth.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“There is a saying that if China attacks [Taiwan], TSMC is the safest place to be since what they do is so valuable,” said Kenny Yang, a former engineer at the company.

A sign for Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. in Shanghai. (Getty Images)

TSMC’s technical prowess is virtually unrivaled. It specializes in manufacturing the industry’s smallest chips — transistors with parts measuring 5 nanometers, the equivalent of two strands of human DNA. Work has already begun on 2-nanometer chips, which also require one of the most complex feats in engineering, an interplay of lasers, molten tin plasma and mirrors known as extreme ultraviolet lithography that a TSMC executive described as “close to black magic.”

Once viewed benignly as an electronic commodity, semiconductors are now vital national security assets in the global race for tech supremacy. Last month, TSMC’s board approved a plan to open a $12-billion foundry in Arizona by 2024, a move seen as a way to placate Trump administration and Pentagon officials who grew uneasy over TSMC’s trade relationship with China.

A chip made by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. is seen at the 2020 World Semiconductor Conference in Nanjing, China. (Getty Images)

By clashing over something as ubiquitous as chips, China and the U.S. risk sparking a conflict that could end-up being far more disruptive than the one that erupted last year over China’s 5G ambitions. U.S. restrictions on exports shattered Chinese-owned Huawei’s plans to roll out 5G networks worldwide and hobbled its once-thriving smartphone business.

Advertisement

Whoever wins access to the leading semiconductors gains a critical advantage in technologies that will define the coming age including A.I., quantum computing and the “internet of things.” These will affect everything from missiles to autonomous vehicles to cybersecurity to the development of new drugs.

“Semiconductors underpin all the ‘must win’ technologies of the 21st century,” said Ashley Feng, a China and Taiwan expert formerly at the Center for a New American Security. “To both the United States and China, being able to dominate in the semiconductor space is crucial to winning the next generation of technology.”

TSMC is entangled in this escalating struggle at a time when China, propelled by rising nationalism at home, regards the U.S. and other Western nations as in decline. The Trump administration has seized on semiconductors as a choke point to slow China’s progress. This year, it announced licenses would be required to export chips that contain American intellectual property, which most silicon wafers do, to Huawei and China’s top chipmaker, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp.

Washington this month blacklisted Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp., accusing it of being a front for the Chinese military and cutting it off from American equipment and investment. That raises the specter of Chinese retaliation against an American company such as Apple, which would in turn hurt TSMC.

Beijing’s suggestion that it might invade Taiwan and return it to Chinese dominion could further imperil TSMC’s freedom. China has long yearned for a company as advanced as TSMC. It has invested billions of dollars and poached hundreds of Taiwanese engineers in a national Manhattan Project-like bid to catch up to Taiwan, South Korea and the U.S. Despite those efforts, China remains years behind and must import all but 15% of its semiconductors, spending more on the technology than on foreign crude oil each year.

The U.S. and other countries are working to keep China at a disadvantage. Washington forced TSMC to cut exports to Huawei’s chip design subsidiary, HiSilicon Technologies, which was its second-biggest customer after Apple, analysts said. And the Trump administration reportedly pressured Taipei to curtail TSMC’s business in China, which accounts for a fifth of the company’s revenue and where it maintains a small foundry.

TSMC is caught in between two superpowers. It needs China for future growth and the U.S. for its technology and its biggest customers today. Dan Wang, analyst at GaveKal Dragonomics in Beijing

Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen, left, and TSMC founder Morris Chang. (Getty Images)

TSMC and the office of Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen have denied facing pressure from the White House.

Advertisement

Founded in 1987 by Morris Chang, a Harvard- and MIT-educated engineer, TSMC has thrived by trying to be the neutral chip foundry of the world. But national interests and global economic pressures have rattled the $412-billion chip industry, which was born out of Silicon Valley in the 1950s and is now dominated by a few deep-pocketed giants such as TSMC, Samsung and Intel, which are able to spend billions each year on research and development to compete.

Those budgets are required to keep pace with what’s known as Moore’s law: the general industry rule that the amount of transistors on a chip doubles every two years, allowing producers to pack more processing power into less space. It’s why the iPhone 12 is 50% faster than the iPhone 11.

If relations between Washington and Beijing remain sour — as they’re expected to under the Biden administration given the bipartisan appeal of a hard-line China policy — experts say an intricate network of chip designers, software programmers, equipment builders and chip assemblers will begin to unravel under mounting pressure to choose between U.S. and Chinese supply chains.

“TSMC is caught in between two superpowers,” said Dan Wang, an analyst at Gavekal Dragonomics in Beijing. “It needs China for future growth and the U.S. for its technology and its biggest customers today.”

The company acknowledges trade tensions have made things harder but remains confident it can come out ahead. By continuing to make advanced chips at a scale no other company except Samsung can replicate, TSMC believes its business can thrive regardless of the geopolitical troubles.

“At the end of the day, you want to be working with the best companies,” said Rick Cassidy, a senior vice president at TSMC. “Nothing in the geopolitical [arena] has any impact on what we’re doing.”

Others don’t share that view. The threat of losing the Chinese market is filling the boardrooms of semiconductor firms with dread, said a U.S.-based executive who spoke on condition of anonymity because he wasn’t authorized to speak to the media.

“It’s very hard for companies to say I’m going to pick a side. Some are hoping they can pick both sides and remain in the middle,” he said. “But in order for us to be commercially competitive, we need access to the China market.”

Nowhere will a chip war be felt more acutely than in Taiwan, where the semiconductor industry accounts for 15% of the economy and the threat of a Chinese invasion looms. The island, which is roughly the size of Maryland and about 100 miles off the coast of China, was occupied by the mainland’s fleeing Nationalist government in 1949 after it was defeated by Mao Zedong’s communist army.

Beijing’s economic and diplomatic muscle has compelled all but a few small nations to shun Taiwan and abide by the one-China policy. The U.S. recognizes that policy in theory, but tensions have soared this year as the Trump administration’s adversarial relationship with Beijing has drawn Taipei and Washington closer.

Advertisement

The U.S. has sold weapons to Taiwan, and Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar this year became the highest-ranking U.S. official to visit Taipei since 1979.

TSMC has tried to be the Switzerland of the chip industry, but those days are over. Craig Addison, author

China’s military has expanded training for a possible assault and flown increasing numbers of warplanes across the Taiwan Strait to exhaust the island’s air defenses. Beijing’s recent crackdown on freedoms in Hong Kong has also eroded what little support remained in Taiwan for unification with the mainland.

TSMC sits on this volatile fault line. Tensions could be further exacerbated if the U.S. maintains pressure on the firm to starve Chinese companies of its valuable chips. If China ever succeeded in uniting with Taiwan — whether peacefully or by force — it could place a stranglehold on Apple and U.S. chipmakers such as Nvidia, Qualcomm, Xilinx and AMD that rely on TSMC’s fabrication plants, or fabs, to produce their designs.

“China could use the disabling of TSMC’s wafer fabs on Taiwan to inflict a heavy blow on the U.S. tech economy, given that all of the U.S. fabless chipmakers, as well as major tech brands like Apple, rely on TSMC for advanced wafer fabrication,” said Craig Addison, author of “Silicon Shield: Taiwan’s Protection Against Chinese Attack.” “TSMC has tried to be the Switzerland of the chip industry, but those days are over.”

Morris Chang, chairman of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., listens during a 2014 shareholders conference in Taipei. (Sam Yeh / AFP/Getty Images)

If we were not around, billions of people around the world would live differently than they do now. Morris Chang, TSMC’s founder

Chang, TSMC’s founder, is accustomed to conflict. Born in Ningbo, China, in 1931, he lived through the Sino-Japanese war, World War II and the Chinese civil war before fleeing for British-controlled Hong Kong and eventually attending college in the U.S. when he turned 18.

After a long career in the U.S. semiconductor industry working for Sylvania and Texas Instruments, where he headed the company’s chip business, he was recruited by the Taiwanese government to run its Industrial Technology Research Institute in 1985.

Taiwan was about to emerge from decades of martial law and needed to innovate its economy. Chang was tasked with upgrading its semiconductor industry. He envisioned a company specializing solely in building chips instead of also designing them under one roof like other firms at the time.

Advertisement

“It was thought that every company needed manufacturing … and that was the most capital-intensive part of a semiconductor company,” Chang said in a 2007 interview with SEMI, a chip industry association. “So I thought that maybe TSMC, a pure-play foundry, could remedy that.”

In doing so, Chang created the world’s first dedicated semiconductor foundry, where American companies could outsource chip production and forgo the heavy cost of building manufacturing facilities. Cassidy, the TSMC North America president, said he knew Chang had something special when he was a customer of the Taiwanese upstart in the 1990s trying to take an American semiconductor fabless.

“I could buy a wafer from TSMC at a price lower than my internal cost,” said Cassidy, a West Point graduate who joined TSMC in 1997. “It included quality, reliability, delivery and service and no charge for process R&D. When I thought about that, it was profound.”

TSMC would lead Taiwan’s emergence as a powerhouse in technology hardware. Chang, who retired in 2018, is regarded in Taiwan as a Steve Jobs- or Bill Gates-type figure and often asked to step in as a statesman on economic affairs. His presence at a banquet for Keith Krach, U.S. undersecretary of State for economic growth, hosted by the Taiwanese president in September underscored the company’s significance.

“If we were not around,” Chang once said of his company, “billions of people around the world would live differently than they do now.”

The tumult in the industry has not hurt TSMC’s bottom line. The company quickly recouped its lost business in China, and its stock price has more than doubled since March. The firm has even embarked on an unprecedented recruitment drive, aiming to make around 8,000 new hires to add to its 50,000-strong workforce.

“They’re the leader in the semiconductor industry and critical to so many big tech firms,” said Charlie Yeh, 22, a student at National Tsing Hua University who attended a recent recruitment drive. “They have the most advanced process in the world. Apple can make the iPhone 12 because of TSMC.”

Whether that success will fall victim to China’s designs remains to be seen. But Chang seemed to have a sense of unease when he delivered a speech at TSMC’s annual employee sports day in November 2019. He warned his former charges that the company could soon be dragged into a contest between major powers.

“When the world is not at peace,” he said, “TSMC will become a key battleground.”

Times staff writer Pierson reported from Singapore and special correspondent Yun from Hsinchu.

Advertisement