Newly opened Vatican archives may give clues to Pope Pius XII’s Holocaust silence

]

]

Sixty lucky historians stood in line at the Vatican on Monday as the tiny city-state finally opened its wartime archives on the papacy of Pius XII — millions of pages that could help explain why the pontiff kept silent during the slaughter of 6 million Jews in the Holocaust.

Vatican archivists took more than 14 years to ready the 2 million documents, which are organized in boxes that officials say stretch for 350 yards when put end to end.

The contents could help settle the question of whether Pius should be remembered for quietly hiding 4,000 Jews from the Nazis in convents and churches — knowing that denouncing Adolf Hitler would make their plight worse — or must be condemned for not speaking out as Jews were gassed in death camps.

Pius was pope from 1939 until his death in 1958. A pope’s archives are usually kept sealed for 70 years after he dies, but Pope Francis sped up their publication, announcing, “The church isn’t afraid of history.”

Advertisement

A view of The Vatican Apostolic Secret Archive, the central archive of the Holy See where are kept all the documents concerning the government and pastoral activity of the Roman pontiff and offices of the Holy See. (Alberto Pizzoli/ AFP)

As historians gathered in Rome over the weekend, ready to get in line, Archbishop Paul Richard Gallagher, the Vatican’s secretary for relations with states, said Pius “emerges as a great champion of humanity, a man deeply concerned about the fate of humankind during those terrible years, somebody who was very sensitive and concerned about those who were being persecuted, somebody who was also the object of the hatred of Nazis and fascism.”

Bishop Sergio Pagano, prefect of the Vatican’s Apostolic Archives, has also suggested there is little cause for shame. “We will leave each person to draw their own conclusions but we have no fear. The good [that Pius did] was so great that it will dwarf the few shadows,” he said recently.

Historians have begged to differ. John Cornwell, the British author of the 1999 book “Hitler’s Pope,” believes Pius made it clear to Hitler he would not speak out against the Holocaust.

Before he become pope and took the name Pius XII, Eugenio Pacelli served as the Vatican’s ambassador to Germany from 1917 to 1929, witnessing the rise of Nazism before he became secretary of state in Rome.

His path has also been studied by David Kertzer, a professor of anthropology and Italian studies at Brown University, who was at the Vatican on Monday and said various archives from different Vatican departments would be ready for inspection.

“An important one is the Apostolic archive, which will have correspondence with the Vatican’s ambassador in Berlin, but also with the ambassador to the fascist government of Benito Mussolini in Italy,” he said.

Kertzer said that he was not looking to solve a mystery about Pius.

Advertisement

“If you want to know if this pope denounced the Nazis for killing most of the Jews in Europe, the answer is he didn’t, and there is nothing in the archive which will tell us different,” he said.

“But there is a lot we need to know about how decisions were made and who took them,” he added.

Kertzer gave as an example the Vatican’s lack of reaction to the Nazis’ rounding up of 1,000 Jews in Rome in October 1943 for transfer to the Auschwitz concentration camp.

“We know the pope was upset and we know he knew they would be killed,” he said. “He had his secretary of state summon the German ambassador and tell him he was unhappy.”

Advertisement

“We also already know that the ambassador replied that the order came from very high up, adding that the Vatican could lodge a complaint, even if it would displease people. The secretary of state effectively responded, ‘No, we’ll leave it to you.’”

“So we know what Pius did and didn’t do. I would like to know in this case what his close advisors were suggesting at the time,” he said.

Kertzer said he also wanted to know more about why Pius did not oppose the 1938 racial laws that were introduced by Mussolini and ejected Jews from public life. “I will be looking to see if people in the Vatican were urging him to take action, whether there was debate,” he said.

“The Nazi regime was persecuting the Catholic Church in Germany and in occupied countries,” he said. “Pius had no love for Hitler and saw his role as defending the church. Other issues were lamentable but they weren’t his responsibility.”

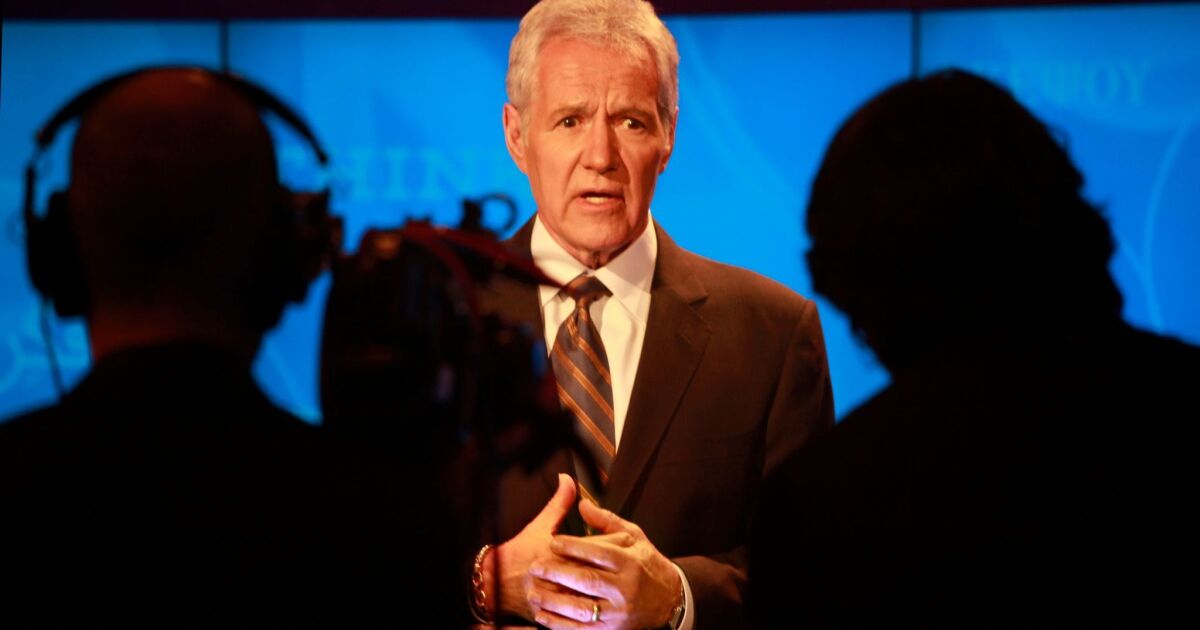

Alex Trebek dead: ‘Jeopardy!’ host and trivia master was 80

Alex Trebek, the master of trivia whose quick wit, easy smile and my-favorite-professor demeanor made “Jeopardy!” a welcome guest in the living rooms of America for decades, has died at his home following a battle with pancreatic cancer, per the quiz show’s Twitter account. He was 80.

The game show host had suffered a series of medical complications in recent years — a heart attack in 2007 and brain surgery for blood clots that formed after he hit his head in a fall in 2018. In early 2019 he revealed he had Stage 4 pancreatic cancer and vowed to beat the disease, joking that he still had three years left on his contract.

But there was urgency in his voice as well. “So help me,” he said on a YouTube video announcing the diagnosis. “Keep the faith and we’ll win.”

Late in the summer of 2019, Trebek — who was candid and open about his fears and the wrenching pain and lingering depression after undergoing rounds of chemotherapy — announced that he was back at work, filming for the upcoming season. “I’m on the mend,” he said, “and that’s all I can hope for.”

Advertisement

As the cancer ebbed and then roared back again, audiences, contestants and viewers seemed to form a nearly familial bond with Trebek, holding up signs of support during tapings, donating to cancer research in his name, lining up just to cheer as he entered the studio. One contestant, stumped by a question on Final Jeopardy, simply wrote, “What is, ‘We love you, Alex!’” on his answer board.

Trebek’s eyes welled up as he softly read the response aloud. “Thank you,” he said.

Relentlessly academic and stodgy in contrast to the more high-octane game shows of the 1980s, “Jeopardy!” had already been canceled once when Trebek arrived in Hollywood in the early 1970s. But somehow, in his hands, the show was a natural fit, and he drove it up the ratings charts where it remained an early evening favorite, even as other shows came and went.

Trebek became such an institution that he was parodied by Will Ferrell on “Saturday Night Live,” played himself on dozens of television shows and was used as a narrative device on television hits such as “Seinfeld.” Even his theme music became an instantly recognizable jingle that signaled, “Hurry up, time’s ticking.”

Born July 22, 1940, George Alexander Trebek grew up in Sudbury, Canada, in northern Ontario where he dreamed of becoming a hockey player. Studious as a child, Trebek graduated from the University of Ottawa with a degree in philosophy and became a regional authority on the controversial separatist movement in Quebec while working as a reporter for Canadian Broadcasting Corp. His ability to speak French put him at an advantage over his colleagues.

And then, on nothing more than a whim, he tumbled into the world of television game shows.

Telegenic and thoughtful, Trebek was put to work on regional shows including “Music Hop,” “Vacation Time,” “Outside/Inside” and the long-running Canadian quiz show “Reach for the Top.”

His material caught the attention of the daytime programming czar at NBC, who was in the process of cleaning out daytime personalities such as Dinah Shore and Art Fleming and any show that fell into the dreaded fiftysomething demographic. “Jeopardy!” then hosted by Fleming, was among the casualties.

Advertisement

Trebek’s first assignment was to host “The Wizard of Odds,” a game that revolved around statistical questions. When that failed to gain traction, it was shelved and Trebek was asked to host “High Rollers,” a gambling-style game. The show was a quick hit and spawned an evening version, also hosted by Trebek.

But the life of a television game show is a fickle one, much like the fate of the contestants, and — in yet another sudden housecleaning move — NBC canceled “High Rollers” as audiences moved on to more frenetic scream-fests such as “Family Feud,” “The Newlywed Game” and “The Gong Show.” “High Rollers” was brought back briefly and then killed for good in 1980, in part to make room for a rising TV personality, David Letterman.

In 1984, Merv Griffin decided to revive “Jeopardy!” and pair it with “Wheel of Fortune” in an early evening time slot. On the advice of Lucille Ball, Griffin asked Trebek to be the host. And on the advice of Griffin’s wife, the format of the show came with a twist — give the contestants the answer, and let them puzzle out the question. Some thought the idea sprung from the so-called quiz show scandals of the 1950s in which contestants were given answers or asked to throw the game.

“She said, ‘Why don’t you give them the answers?’ And he said, ‘Are you crazy? That’s what got us in trouble with the government,’ ” Trebek explained to NPR’s Rachel Martin in a 2016 interview.

Advertisement

“And then she said ‘The answer is 5,280.’ He said, ‘How many feet are in a mile?’ That was the beginning of ‘Jeopardy!’”

Alex Trebek in Las Vegas in 2000, showing off the new “Jeopardy” slot machines. (Steve Marcus / Associated Press)

As the quiz show rolled through the decades, surviving upstart challengers including “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire” and programming shifts, Trebek remained a comfortable fit with audiences — fatherly, dependable, the keeper of all questions. In a 2014 Reader’s Digest poll, Trebek ranked as the eighth-most trusted person in the United States, right behind Bill Gates and 51 steps above Oprah Winfrey.

At home, Trebek said, he preferred to watch the Lakers or hockey games rather than his own show. And on weekends he liked to drift through Home Depot, looking for whatever gadget or gizmo might be handy for a home improvement project. Sometimes he and his wife would retreat to their lake house in Paso Robles to escape the crush of the city.

Advertisement

In front of the camera, Trebek at times seemed as though he’d stepped straight from “Masterpiece Theatre.” He never hugged guests, kept small talk to a minimum, announced categories with grave seriousness and let contestants know their fate with a curt “Correct” or “No.”

But during breaks, he would seemingly flip a switch and become bubbly, urging those in the audience to ask him questions.

“When are you going to retire?” someone in the crowd called out when a Washington Post reporter was watching the taping in 2016.

“When am I going to retire? Jeez. I never liked you,” he joked.

Advertisement

“How do you prepare for every taping?” another person wondered.

“I drink,” he replied. “And I’m going to do that now.”

Trebek said he enjoyed hosting the show because he liked being in the company of smart people, those fluid enough to pivot from Samuel Taylor Coleridge to Tupac Shakur, from the fictional kingdom of Narnia to the Curse of the Billy Goat at Chicago’s Wrigley Field.

It remained a puzzle, though, whether Trebek was an intellectual himself, though he was bookish and sometimes surprised those who visited him in the dressing room when he would suddenly start talking about ancient Alexandria or sketch out the solar system on a piece of paper while talking about a book he’d recently read on the history of the universe.

Advertisement

When fellow game show host Steve Harvey questioned whether Trebek was really as smart as viewers seemed to think he was, Trebek challenged Harvey to a trivia showdown. Harvey never brought the matter up again.

A lifelong insomniac, Trebek said he would often retreat to his den and read or work on crossword puzzles until the predawn hours, when sleep finally overtook him. He admitted that he was sometimes so sleep-deprived that he would nod off while stopped at a traffic light.

“It’s a scary way to live,” he said.

In a typical workweek, Trebek would tape up to five shows every Tuesday and Wednesday, arriving at the studios around 9 a.m. and heading back to his Studio City home a little after 6 p.m.

Advertisement

The schedule allowed him to spend time with his children when they were young, and then to travel with his wife when they were grown.

When he arrived at the studios for work, Trebek would retreat to his dressing room and spend several hours reviewing the 300-plus questions that researchers came up with each taping day, testing himself along the way. On average, he said, he got 65% to 70% correct.

The hundreds of thousands of clues uttered by Trebek on “Jeopardy!” over the years are cataloged on fan websites like museum pieces, a mountain of trivia that can’t possibly be scaled. As of January 2020, Albert Einstein had been the subject of 302 questions, the Beatles 562 and Jupiter or its moons 319. And perhaps only Trebek pondered each one.

“My life has been a quest for knowledge and understanding, and I am nowhere near having achieved that,” Trebek said in a 2012 interview with The Times. “And it doesn’t bother me in the least. I will die without having come up with the answers to many things in life.”

Advertisement

Trebek is survived by his wife, Jean Currivan, and two children, Matthew and Emily.

Nick Cave Is the Most Joyful, and Critical, Artist in America

]

]

THE INAUGURATION OF Nick Cave’s Facility, a new multidisciplinary art space on Chicago’s Northwest Side, has the feeling of a family affair. In April, inside the yellow-brick industrial building, the classical vocalist Brenda Wimberly and the keyboardist Justin Dillard give a special performance for a group that includes local friends, curators and educators, as well as Cave’s high school art teacher, Lois Mikrut, who flew in from North Carolina for the event. Outside, stretching across the windows along Milwaukee Avenue, is a 70-foot-long mosaic made of 7,000 circular name tags with a mix of red and white backgrounds, each of them personalized by local schoolchildren and community members. They spell out the message “Love Thy Neighbor.”

The simple declaration of togetherness and shared purpose is a mission statement for the space, a creative incubator as well as Cave’s home and studio, which he shares with his partner, Bob Faust, and his older brother Jack. It’s also a raison d’être for Cave, an uncategorizable talent who has never fit the mold of the artist in his studio. Best known for his Soundsuits — many of which are ornate, full-body costumes designed to rattle and resonate with the movement of the wearer — his work, which combines sculpture, fashion and performance, connects the anxieties and divisions of our time to the intimacies of the body.

[Sign up here for the T List newsletter, a weekly roundup of what T Magazine editors are noticing and coveting now.]

Exhibited in galleries or worn by dancers, the suits — fanciful assemblages that include bright pelts of dyed hair, twigs, sequins, repurposed sweaters, crocheted doilies, gramophones or even stuffed sock-monkey dolls, their eerie grins covering an entire supersize garment — are compulsively, unsettlingly decorative. Some are amusingly creature-like; others are lovely in an almost ecclesiastical way, bedecked with shimmering headpieces embellished with beads and porcelain birds and other discarded tchotchkes he picks up at flea markets. Even at the level of medium, Cave operates against entrenched hierarchies, elevating glittery consumer detritus and traditional handicrafts like beadwork or sewing to enchanting heights.

The artist recalls the first time he saw Barkley L. Hendricks’s painting “Steve” (1976). By Scott J. Ross

In invigorating performances that often involve collaborations with local musicians and choreographers, the Soundsuits can seem almost shaman-esque, a contemporary spin on kukeri, ancient European folkloric creatures said to chase away evil spirits. They recall as well something out of Maurice Sendak, ungainly wild things cutting loose on the dance floor in a gleeful, liberating rumpus. The surprising movements of the Soundsuits, which change depending on the materials used to make them, tend to guide Cave’s performances and not the other way around. There is something ritual-like and purifying about all the whirling hair and percussive music; the process of dressing the dancers in their 40-pound suits resembles preparing samurai for battle. After each performance, the suits made of synthetic hair require tender grooming, like pets. Cave’s New York gallerist, Jack Shainman, recalls the time he assisted in the elaborate process of brushing them out — “I was starting to bug out, because there were 20 or 30 of them” — only to have Cave take over and do it all himself. Much beloved and much imitated (as I write this, an Xfinity ad is airing in which a colorful, furry-suited creature is buoyantly leaping about), they can be found in permanent museum collections across America.

Their origins are less intellectual than emotional, as Cave tells it, and they’re both playful and deadly serious. He initially conceived of them as a kind of race-, class- and gender-obscuring armature, one that’s both insulating and isolating, an articulation of his profound sense of vulnerability as a black man. Using costume to unsettle and dispel assumptions about identity is part of a long tradition of drag, from Elizabethan drama to Stonewall and beyond; at the same time, the suits are the perfect expression of W.E.B. Du Bois’s idea of double consciousness, the psychological adjustments black Americans make in order to survive within a white racist society, a vigilant, anticipatory awareness of the perceptions of others. It’s no coincidence that Cave made the first Soundsuit in 1992, after the beating of Rodney King by the Los Angeles Police Department in 1991, a still-vivid racial touchstone in American history; almost three decades later, the suits are no less timely. “It was an almost inflammatory response,” he remembers, looking shaken as he recalls watching King’s beating on television 28 years ago. “I felt like my identity and who I was as a human being was up for question. I felt like that could have been me. Once that incident occurred, I was existing very differently in the world. So many things were going through my head: How do I exist in a place that sees me as a threat?”

Cave had begun teaching at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, with its predominately white faculty, two years before, and in the aftermath of the incident, followed by the acquittal of the officers responsible, he felt his isolation painfully. “I really felt there was no one there I could talk to. None of my colleagues addressed it. I just felt like, ‘I’m struggling with this, this is affecting my people.’ I would think that someone would be empathetic to that and say, ‘How are you doing?’ I held it all in internally. And that’s when I found myself sitting in the park,” he says. In Grant Park, around the corner from his classroom, he started gathering twigs — “something that was discarded, dismissed, viewed as less. And it became the catalyst for the first Soundsuit.”

For many years after he began making his signature work, Cave deliberately avoided the spotlight, shying away from an adoring public: “I knew I had the ability, but I wasn’t ready, or I didn’t want to leave my friends behind. I think this grounded me, and made me an artist with a conscience. Then, one day, something said, ‘Now or never,’ and I had to step into the light.” Initially, he wasn’t prepared for the success of the Soundsuits. For much of the ’90s, “I literally shoved all of them into the closet because I wasn’t ready for the intensity of that attention,” Cave says. He began exhibiting the Soundsuits at his first solo shows, mostly in galleries across the Midwest; he’s since made more than 500 of them. They’ve grown alongside Cave’s practice, evolving from a form of protective shell to an outsize, exuberant expression of confidence that pushes the boundaries of visibility. They demand to be seen.

From left: a 2012 Soundsuit made from buttons, wire, bugle beads, wood and upholstery; a 2013 Soundsuit made from mixed media including a vintage bunny, safety-pin craft baskets, hot pads, fabric and metal; a 2009 Soundsuit made from human hair; a 2012 Soundsuit made from mixed media including sock monkeys, sweaters and pipe cleaners. All images © Nick Cave. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photos by James Prinz Photography

From left: “Speak Louder,” a 2011 Soundsuit sculpture made from buttons, wire, bugle beads, upholstery and metal; a 2010 Soundsuit made from mixed media including hats, bags, rugs, metal and fabric; a 1998 Soundsuit made from mixed media including twigs, wire and metal. All images © Nick Cave. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photos by James Prinz Photography

Following the phenomenal success of the Soundsuits, Cave’s focus has expanded to the culture that produced them, with shows that more directly implicate viewers and demand civic engagement around issues like gun violence and racial inequality. But increasingly, the art that interests Cave is the art he inspires others to make. With a Dalloway-like genius for bringing people from different walks of life to the table in experiences of shared good will, Cave sees himself as a messenger first and an artist second, which might sound more than a touch pretentious if it weren’t already so clear that these roles have, for some time, been intertwined. In 2015, he trained youth from an L.G.B.T.Q. shelter in Detroit to dance in a Soundsuit performance. The same year, during a six-month residency in Shreveport, La., he coordinated a series of bead-a-thon projects at six social-service agencies, one dedicated to helping people with H.I.V. and AIDS, and enlisted dozens of local artists into creating a vast multimedia production in March of 2016, “As Is.” In June 2018, he transformed New York’s Park Avenue Armory, a former drill hall converted into an enormous performance venue, into a Studio 54-esque disco experience with his piece — part revival, part dance show, part avant-garde ballet — called “The Let Go,” inviting attendees to engage in an unabashedly ecstatic free dance together: a call to arms and catharsis in one. Last summer, with the help of the nonprofit Now & There, a public art curator, he enlisted community groups in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood to collaborate on a vast collage that will be printed on material and wrapped around one of the area’s unoccupied buildings; in September, also in collaboration with Now & There, he led a parade that included local performers from the South End to Upham’s Corner with “Augment,” a puffy riot of deconstructed inflatable lawn ornaments — the Easter bunny, Uncle Sam, Santa’s reindeer — all twisted up in a colossal Frankenstein bouquet of childhood memories. Cave understands that the lost art of creating community, of joining forces to accomplish a task at hand, whether it’s beading a curtain or mending the tattered social fabric, depends upon igniting a kind of dreaming, a gameness, a childlike ability to imagine ideas into being. But it also involves recognizing the disparate histories that divide and bind us. The strength of any group depends on an awareness of its individuals.

FACILITY IS THE next iteration of that larger mission, and Cave and Faust, a graphic designer and artist, spent years looking for the right space. Creating it required a great deal of diplomacy and determination, as well as an agreeable alderman to assist with the zoning changes and permits. And while it evokes Warhol’s Factory in name, in intent, the approximately 20,000-square-foot former mason’s workshop has a very different cast.

“Facilitating, you know, projects. Energies. Individuals. Dreams. Every day, I wake up, he wakes up, and we’re like, ‘O.K. How can we be of service in a time of need?’” says Cave, who gave me a tour in the fall of 2018, not long after he and Faust settled into the space. Dressed entirely in black — leather pants and a sweater, and sneakers with metallic accents — the 60-year-old artist has a dancer’s bearing (he trained for several summers in the early ’80s at a program in Kansas City run by the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater) and an aura of kindness and irrepressible positivity. One wants to have what he’s having. “Girl, you can wear anything,” he reassures me when I fret about the green ruched dress I’m wearing, which under his discerning gaze suddenly strikes me as distinctly caterpillarlike. It comes as no surprise that Cave’s favorite adjective is “fabulous.”

Vintage bird figurines in the artist’s studio. Renée Cox

In contrast to his maximalist art practice, his fashion tastes have grown more austere, as of late, and include vintage suits and monochrome classics from Maison Margiela, Rick Owens and Helmut Lang. “I have a fabulous sneaker collection,” he says. “But you know, the reason why is because those floors at the school are so hard,” he says, referring to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he is now a professor of Fashion, Body and Garment. (I also teach at the school, in a different department.) “I can’t wear a hard shoe, I have to wear a sneaker,” he says. Faust teases him: “I love how you’ve just justified having that many sneakers.”

Cave met Faust, who runs his own business from Facility, in addition to supporting the artist as his special projects director, when he happened to stop by a sample sale of Cave’s clothing designs in the early 2000s. The Soundsuits are, for all intents and purposes, a kind of clothing, so fashion has been a natural part of Cave’s artistic practice since the beginning — he studied fiber arts as an undergraduate at the Kansas City Art Institute, where he first learned to sew. In 1996, he started a namesake fashion line for men and women that lasted a decade. If the Soundsuits resist categorization as something to wear in everyday life, they arrive at their unclassifiable beauty by taking the basic elements of clothing design — stitching, sewing, understanding how a certain material falls or looks with another kind of material — and exaggerating them into the realm of atmospheric psychedelia. That he teaches in the fashion department at an art school further underscores the thin line Cave has always walked between clothing and sculpture, all of it preoccupied in some way with the human body, its form and potential energy. His own clothing designs are slightly — only slightly — more practical variations on the Soundsuits: loud embroidered sweaters, crocheted shirts with sparkly jewelry. “He came in and was like, ‘These clothes are so out there, I can’t wear any of this,’” Cave recalls, laughing. (Faust politely bought a sweater and still wears it today.) At the time, the artist was about to publish his first book and asked Faust to design it; the collaboration was a success, and Faust has subsequently designed all of Cave’s publications. About eight years ago, the nature of the relationship changed. “Before that, I was single for 10 years. I was always traveling, and who is going to handle all of that?” Cave says. “But Bob already knew who I was, and that makes all the difference. Being with someone who is a visionary in his own right and using this platform as a place of consciousness — it’s very important to me.”

In this clip from Cave’s “Here,” the artist’s Soundsuits are captured in Detroit. © Nick Cave. Courtesy of The Artist And Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Upstairs is the couple’s living space and selections from Cave’s personal art collection: a Kehinde Wiley here, a Kerry James Marshall there. (A lesson from Cave: Buy work from your friends before they become famous.) Cave and Faust opted to leave the floors and walls scarred, bearing the traces of its former use as an industrial building. In a small, sunny room off the kitchen, one corner of the ceiling is left open to accommodate an abandoned wasp’s nest, a subtle, scrolled masterpiece of found architecture. Faust’s teenage daughter also has a bedroom, and Jack, an artist with a design bent, has an adjacent apartment.

Downstairs, in the cavernous work space big enough to host a fashion show, musical or dance performance, are Cave’s and Faust’s studios. Some of Cave’s assistants — he has six of them, Faust has one — are applying beads on a vast, multistory tapestry, a project for Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport called “Palimpsest.” “It’ll all be gathered and bustled, so there’s layers and layers of color. Kind of like an old billboard that, over time, weathers, and layers come off and you see the history,” Cave explains. A front gallery is a flexible space where video art visible from the street could be projected — a nod to Cave’s first job out of art school, designing window displays for Macy’s — or young artists could be invited to display work around a shared theme. Facility has already established an art competition and prizes for Chicago Public School students and funded a special award for graduate fashion students at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. “There are lots of creative people that do amazing things but just have never had a break,” Cave says. “And so to be able to host them in some way, these are the sort of things that are important to us, so we thought, ‘Why not?’”

AWKWARD PERSONAL disclosures. Long evaluative silences. Talk of “coming to form.” Art-school crits — sessions in which a professor reviews his students’ work — are all pretty similar, but Cave’s are famous both for their perspicacity and warmth. For all his multi-hyphenates, “teacher” may be the role that best sums up his totality of being. “When someone believes in your work, it changes how you see your future,” he says when we meet in the vast, light-filled studios in downtown Chicago, where the graduate fashion students are working.

It’s the second-to-last crit of the year for Cave’s first-year students in the two-year M.F.A. program, and the pressure is on to develop their own distinct visual language before they begin their thesis projects in the fall. One woman from Russia has made a set of dresses from delicate organic 3-D-printed shapes — mushrooms, flowers — sewing them together and arranging them on a mannequin; they resemble exquisite body cages. Cave suggests that she should work in muslin on a flat surface rather than directly on the mannequin in order to make the silhouette “less uptight.”

Cave’s “Untitled” (2018), which features a carved head and an American flag made of used shotgun shells. Image © Nick Cave. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photo by James Prinz Photography

Next up is a student from China, who directs our attention to an anchor-shaped object suspended from the ceiling. It is made of small blue squares of fabric she’s dipped in batter and deep-fried to stiffen. She plays Björk’s “The Anchor Song” for us on her iPhone and explains that the textile sculpture is an expression of homesickness, longing and the mourning of a long relationship. We stare up at it silently. There’s a faint whiff of grease. After some back and forth with the student, Cave delivers his verdict: “Your tent is big, but you need to get on your boxing gloves and get in there,” he says. “You should be completely, 100 percent in it, and not let your will dictate. Bring all the parts together.”

“That was pretty raw,” says Cave, once we are back in his office, noting that, when given a push, the student with the anchor astonishes everyone with what she can do. He clearly adores all of his charges, and sees teaching as a way of passing on his own teachers’ lessons: a way of liberating the creative subconscious within the technical rigors of design. “You’re looking at what’s there — fabric, shape and form — and asking, ‘How are you coming to pattern, how are you coming to design?’ And some have just opened up for the first time, and the moment you open up, there are bigger questions, there’s a lot more responsibility, there’s so much more to grapple with.”

A second-year student, Sean Gu, stops by to say hello. He’s just returned from China with a suitcase full of completed samples he wants to show Cave. The garments, jackets and vests, have zips and seat-belt-like buckles and artfully drooping corners that were inspired by Chinese political slogans. Cave and I take turns trying them on: One piece, a vest made of reflective polyurethane with multiple armholes and zippers, is our favorite. (Cave wore it best, of course.) The look on his face is one of pure delight in the cool, fabulous thing his student has made.

Where, one might ask, did Cave’s seemingly boundless reservoirs of optimism and joy and productive energy come from? The short answer is Missouri, where Cave, born in Fulton, in the central part of the state, and raised in nearby Columbia, was the third of seven brothers. His mother, Sharron Kelly, worked in medical administration (Cave’s parents divorced when he was young), and his maternal grandparents lived nearby on a farm filled with animals. “Now that I look back, it was really so amazing for my brothers and myself to be in the presence of all of that unconditional love,” he says. “We were rambunctious, and of course you fight with your brothers, but we always made up through hugging or kissing. It was just part of the infrastructure.” Personal space was limited but respected, a chart of chores was maintained, and creative projects were always afoot (his aunts are seamstresses; his grandmother was a quilter). Hand-me-downs were individually customized by each new wearer. “I had to find ways of finding my identity through deconstructing,” he recalls. “So, if I didn’t want to be in my brother’s jacket, I’d take off the sleeves and replace it with plaid material. I was already in that process of cutting and putting things back together and finding a new vocabulary through dress.”

A detail of Cave’s 2019 “Augment” installation, made from inflatable lawn ornaments. Renée Cox

The artist tells an illuminating story about his mother, who managed the household on one income and would still often find ways to send food to a struggling family in the neighborhood. Once, during a particularly tight month, she came home from work to realize that there was no food left in the house except dried corn. And so she made a party of it, showing her sons a movie on television and popping the corn. “It doesn’t take much to shift how we experience something,” says Cave, recalling how she would entertain them simply by putting a sock on her hand and changing her voice to create a character. “It’s nothing, but it’s everything,” he says. “You’re just totally captivated. It’s these moments of fantasy and belief that’s also informed how I go about my work.”

Fashion’s transformative power was also something he understood young, beginning with watching his older female relatives attend church in their fancy hats. In high school, Cave and Jack, who is two years older, experimented with platform shoes and two-tone flared pants. High fashion came to town, literally, via the Ebony Fashion Fair, a traveling show launched and produced between 1958 and 2009 by Eunice W. Johnson, the co-founder of Johnson Publishing Company, which published Ebony and Jet magazines, both cultural bibles for black America. “Ebony magazine was really the first place we saw people of color with style and power and money and vision, and that fashion show would travel to all of these small towns,” he reminisces. “Honey, black runway back in the day was a spectacle. It’s not just walking down the runway. It was almost like theater. And I’m this young boy just eating it up and feeling like I’m just in a dream, because it’s all fabulous and I just admire beauty to that extreme. I was just completely consumed by that.” His high school teachers encouraged him to apply to the Kansas City Art Institute, where he and Jack would stage fashion shows, which felt more like performance pieces thanks to Cave’s increasingly outré clothing designs. “I just had what I needed to have in order to be the person I need to be,” Cave says.

Also harrowingly formative to Cave’s outlook was the AIDS crisis, which was at its deadly height while he was in graduate school at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan in the late ’80s. He became painfully aware of the function of denial in our culture, and the extent of people’s unwillingness to see. “Watching my friends die played a big part in my perspective,” he says. “In those moments, you have a choice to be in denial with them or to be present, to be the one to say, ‘This is happening.’ You have to make a decision to go through that process with them, to pick up their parents at the airport, to clean to get their apartments ready for their parents to stay. And then you have to say goodbye, and then they’re gone, and you’re packing up their belongings to send to their families. And then you’re just left there in an empty apartment, not knowing what to feel.” In a single year, he lost five friends and confronted his own mortality waiting for his test results. “Just — choosing not to be in denial in any circumstance,” he says.

THE VULNERABILITY OF the black body in a historically white context is a subject generations of African-American artists have contended with, perhaps most iconically in Glenn Ligon’s 1990 untitled etching, in which the phrase “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background,” adapted from Zora Neale Hurston’s 1928 essay “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” is printed over and over again in black stencil on a white canvas, the words blurring as they travel the length of the canvas. In her book “Citizen: An American Lyric” (2014), the poet Claudia Rankine, writing about Serena Williams, puts it this way: “The body has a memory. The physical carriage hauls more than its weight. The body is the threshold across which each objectionable call passes into consciousness — all the unintimidated, unblinking and unflappable resilience does not erase the moments lived through, even as we are eternally stupid or everlastingly optimistic, so ready to be inside, among, a part of the games.”

The individual body has a memory, and so do collective bodies, retaining a longer and longer list of names — Eric Garner on Staten Island, Michael Brown in Missouri, Trayvon Martin in Florida and so many more innocent black people who have suffered violence and death at the hands of police — within it. But that day in 1992, hurrying back to his studio with a cart full of twigs and setting out to build a sculpture from them, Cave had no idea that the result would be a garment. “At first, it didn’t occur to me that I could wear it; I wasn’t thinking about it.” When he finally did put it on and moved around, it made a sound. “And that was the beginning,” he says. “The sound was a way of alarming others to my presence. The suit became a suit of armor where I hid my identity. It was something ‘other.’ It was an answer to all of these things I had been thinking about: What do I do to protect my spirit in spite of all that’s happening around me?” Throughout the Soundsuits’ countless iterations, Cave has tinkered with their proportions, thinking about the shapes of power, constructing forms that recall a pope’s miter or the head of a missile. Some of them are 10 feet tall.

But no matter their variations, these Soundsuit designs have always felt personal and unique, as if only Cave himself could have invented them. And yet he is also aware of how the pain he is addressing in these works is also written into our culture: There is a long lineage of casual cruelty that has shaped Cave’s art. His 2014 installation at Jack Shainman Gallery, “Made by Whites for Whites,” was inspired by an undated ceramic container Cave found in a flea market that, when pulled off the shelf, revealed itself to be the cartoonishly painted disembodied head of a black man. “Spittoon,” read the label. Renting a cargo bay, Cave toured the country in search of the most racially charged memorabilia he could find. The centerpiece of the show, “Sacrifice,” features a bronze cast of Cave’s own hands and arms, holding another severed head, this one part of an old whack-a-mole type carnival game — simultaneously lending compassion to the object while implicating its beholder. Look, Cave is saying. If we’re ever going to move past this hatred, we have to acknowledge what it is that produced it.

A collection of racially charged salt and pepper shakers that Cave found in a flea market and keeps in his studio. Renée Cox

“It’s not that Nick doesn’t have a dark side,” Denise Markonish, the senior curator and managing director of exhibitions at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art in North Adams, Mass., tells me. Markonish approached Cave in 2013 about planning an exhibition for the museum’s largest gallery. “He wants to seduce you and punch you in the gut.” The result, the artist’s most ambitious seduction to date, was his 2016 show, “Until,” a twist on the legal principle of innocence until guilt is proven. For it, Cave transformed the football-field-size room into a sinister wonderland, featuring a vast crystal cloudscape suspended 18 feet into the air made up of miles of crystals, thousands of ceramic birds, 13 gilded pigs and a fiberglass crocodile covered in large marbles. Accessible by ladder, the top of the cloud was studded with cast-iron lawn jockeys, all of them holding dream catchers. It’s an apt and deeply unsettling vision of today’s America, land of injustice and consumer plenty, distracted from yet haunted by all of the things it would prefer not to see.

While they were sourcing the materials for the show, Markonish tells me, they realized how expensive crystals are, and one of the curators, Alexandra Foradas, called Cave to ask if some of them could be acrylic. “He said, ‘Oh, absolutely, 75 percent can be acrylic but the remaining 50 percent should be glass.’ She said, ‘Nick, that’s 125 percent,’ and without pausing he said, ‘Exactly.’” After the show, Markonish asked Cave and Faust to create a graphic expression of the exhibition, which resulted in a tattoo on the inside of her index finger that reads “125%.” “Of course, at that point, it wasn’t about his use of material,” she says, “but about his dedication and generosity. It was his idea to open up his exhibition to people from the community, to performers or for discussions about the difficult things he wants to talk about in his work.”

One of those themes is the gun violence that has ravaged many black communities; Chicago, Cave’s home of three decades, had more shooting victims (2,948) in 2018 than Los Angeles (1,008) and New York (897) combined, largely concentrated in a handful of neighborhoods on the South and West Sides. (Cave had hoped to open Facility on Chicago’s racially diverse West Side, only to run into intransigent zoning laws; he wants to find a permanent home there for “Until” and has art projects planned with the area’s high schools.) Cave’s most recent gallery show, “If a Tree Falls,” which featured sculptural installations and opened at Jack Shainman Gallery in fall 2018, strikes a more somber, elegiac note than his previous work, juxtaposing body parts in bronze monochrome, including casts of his own arms emerging from the gallery walls, holding delicate flower bouquets, which suggest a sense of renewal, of hope and metamorphosis. He’s now working on a new series of bronze sculptures, which include casts of his own hands, topped with cast tree branches, birds and flowers, the first of which is meant to debut at Miami’s Art Basel in December. The sculptures will be on a much bigger scale — a human form made larger than life with embellishment, not unlike the Soundsuits in approach but with a new sense of gravity and monumentality (they are intended to be shown outdoors). The man famous for bringing a light touch to the heaviest of themes is, finally, stripping away the merry trappings and embracing the sheer weight of now.

“Arm Peace,” part of a series of sculptures created for Cave’s 2018 solo show, “If a Tree Falls,” at Jack Shainman Gallery. Renée Cox A detail of “Tondo” (2019). Renée Cox

When I ask Cave how he feels about the critical reception of his work — he is one of that select group of artists, like Jeff Koons or David Hockney, who is celebrated by both high art and popular culture — he tells me that he stopped reading his shows’ reviews, but not because he’s afraid of being misunderstood or underappreciated; instead, he seems to be objecting to a kind of critical passivity. “What I find peculiar is that no one really wants to get in there and talk about what’s behind it all,” he says. “It’s not that I haven’t put it out there. And I don’t know why.”

I push him to clarify: “Do you mean that a white reviewer of your show might explain that the work provides commentary on race and violence and history but won’t extend that thinking any further, to his or her own cultural inheritance and privilege?”

“They may provide the context, but it doesn’t go further. They’re not providing any point of view or perspective, or sense of what they’re receiving from this engagement. I just think it’s how we exist in society,” he replies.

One of the four covers of T’s 2019 Greats issue Renée Cox

Is art alone enough to shake us from our complacency? Two decades into a new millennium, these questions have fresh urgency: By turning away from stricken neighborhoods and underfunded schools, we’ve perpetuated the conditions of inequality and violence, effectively devaluing our own people. We’ve dimmed the very kind of 20th-century American dreaming that led so many of us, including Cave, to a life filled with possibility. Whether or not this can be reversed depends on our being able to look without judgment and walk without blinders, he believes. It means reassessing our own roles in the public theater. It means choosing not to be in denial or giving in to despair. It means seeing beyond the self to something greater.

“I just want everything to be fabulous,” he tells me, as we part ways for the afternoon. “I want it to be beautiful, even when the subject is hard. Honey, the question is, how do you want to exist in the world, and how are you going to do the work?”