Penn President Nominated as Ambassador to Germany

]

]

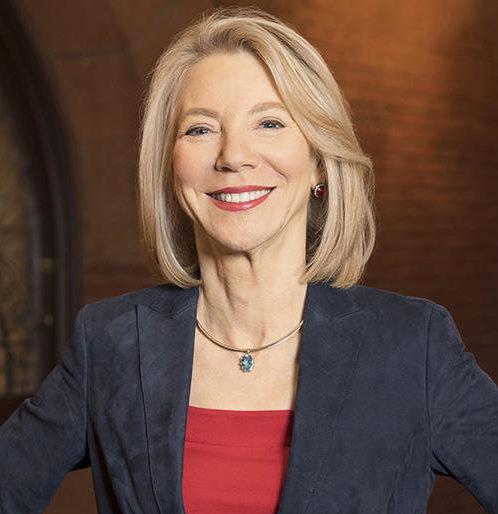

President Joe Biden nominated University of Pennsylvania President Amy Gutmann on July 2 to serve as the United States ambassador to Germany.

If confirmed, Gutmann, who is Jewish, would be the first woman to serve as U.S. ambassador to Germany, and she would likely conclude her 18-year tenure in 2022 as Penn’s longest-serving president.

“As the daughter of a German Jewish refugee, as a first-generation college graduate, and as a university leader devoted to advancing constitutional democracy,” Gutmann said in a statement, “I am grateful beyond what any words can adequately express to President Biden for the faith he has placed in me to help represent America’s values and interests to one of our closest and most important European allies.”

Gutmann’s father, Kurt Gutmann, was born in Nuremberg, Bavaria, and fled Nazi Germany in 1934 to Bombay, India, before moving to New York, where Amy Gutmann was born.

Her father’s refugeedom left a lasting impact on Gutmann.

“The biggest influences on me for leading preceded my ever even thinking of myself as a leader — particularly my father’s experience leaving Nazi Germany,” Gutmann said in a 2011 New York Times interview. “To me, those two things are really important about leadership, to have courage and to be farsighted in your vision, not to be just reacting to the next small challenge.”

After graduating from Radcliffe College of Harvard University in 1971, Gutmann earned a master’s degree in political science at the London School of Economics in 1972 and a doctorate in political science from Harvard University in 1976.

Gutmann’s tenure was marked by her creation of the Penn Compact, a series of initiatives prioritizing inclusion through the expansion of need-based financial aid; innovation through the creation of the Penn Center for Innovation and the Pennovation Works industrial site; and impact, by investing in projects to build connections in Philadelphia, the U.S. and internationally, such as a $100 million gift to the School District of Philadelphia.

She also launched the Making History campaign in 2007, a fundraising effort that raised $4.3 billion before its conclusion in 2012.

In total, Penn’s endowment has grown more than $10 billion during Gutmann’s tenure, helping to bolster Penn as Philadelphia’s largest private employer.

However, Gutmann’s actions as president were not without criticism, including for refusing to take a pay cut from her $3.7 million salary during the pandemic, as several of her Ivy League peers had done. And after the Penn Museum’s announcement that it had, for decades, kept the remains of children killed in the 1985 MOVE bombing, protesters gathered outside of Gutmann’s home.

Gutmann’s appointment as ambassador requires confirmation by the Senate and the approval of German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier.

Though Gutmann has not previously held a government position, she is no stranger to foreign policy or to her nominator.

Under Gutmann, the Penn Biden Center for Diplomacy and Global Engagement was founded in 2016. It opened in 2018 and has continued Penn’s focus on diplomacy, foreign policy and national security.

Gutmann announced Biden as the Benjamin Franklin Presidential Practice Professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and Biden was tasked with leading the center.

Should Gutmann become ambassador, she would replace Robin Quinville, the chargé d’Affaires — and de facto ambassador — of the U.S. Embassy in Germany, who took over for Ambassador Richard Grenell after he resigned in June 2020.

Grenell, known as the “undiplomatic diplomat” in Germany for his dubious etiquette, urged Germany to increase its military defense spending; he and President Donald Trump threatened U.S. military troop withdrawal from Germany and withdrawal from NATO. Grenell also advocated for a ban of Hezbollah in Germany, which took effect in April 2020.

As ambassador, Gutmann would be tasked with navigating issues such as Germany’s defense spending and U.S. sanctions on the $11 billion Nord Stream 2 pipeline.

Gutmann’s appointment as ambassador would resurrect a longstanding tradition of academics serving as ambassadors. In the 1940s and ’50s, former Harvard president James Conant soothed the U.S.-German relationship after the war by engaging with local German universities.

Along with Gutmann, Biden nominated David Cohen, former Penn Board of Trustees chair, to serve as U.S. ambassador to Canada. Scott Bok, investment banker and CEO of Greenhill & Co., Inc., replaced him as chair on July 1.

Bok spoke on behalf of the board, expressing his support for Gutmann.

“She is one of the most highly regarded academic leaders in the world and has led the University of Pennsylvania to new heights of eminence,” Bok said. “Amy has been a superb president for Penn, and we have total confidence that she will remain fully focused on advancing Penn’s agenda until the conclusion of her time at the university.”

[email protected] | 215-832-0741

As Prepared Remarks for Ambassador Stephanie S. Sullivan’s visit to U.S. Bunge Loders Croklaan’s shea Processing Facility

]

]

Ambassador Stephanie S. Sullivan’s visit to

Bunge Loders Croklaan’s shea Processing Facility

July 13, 2021 | 10:00 a.m. – 12:20 p.m. GMT

Tema Free Zones Enclave, Tema

Santanu Bhuyan, Bunge General Manager, West Africa;

Aaron Andu, Managing Director, Global Shea Alliance;

Simon Madjie, Executive Director, American Chamber of Commerce;

Distinguished guests, friends, colleagues, ladies and gentlemen, all protocols – including COVID-19 protocols – observed:

Akwaaba, and Good morning!

I’m pleased to visit you at Bunge Loders Croklaan’s new shea processing factory in Tema. The U.S. government, through the United States Agency for International Development, or USAID, has supported the establishment and growth of the shea industry worldwide, through the Global Shea Alliance over the past decade, to strengthen the organization and mobilization of the private sector and other stakeholders to address the multiple shared challenges the industry faces.

Since my arrival in Ghana at the end of 2018, I have experienced a fascinating journey along the shea supply chain path. Given the impact of the industry on improving incomes for women and their families, it’s been wonderful to witness first-hand the enormous growth of the shea export industry in Ghana. I planted shea seedlings at my home last year and will join women in Damongo, capital of the Savannah Region, soon, to transplant the seedlings into designated managed parklands. I have participated in the opening of two, new, handcrafted shea processing facilities in Northern Ghana, where the women showed me some of the difficult steps involved in manually processing shea nuts into butter.

These were all a result of productive public private partnerships. Today, I am happy to visit the only shea fractionation plant in Africa, which is located right here in Ghana, made possible by the investments of a U.S. company, Bunge Loders Croklaan. Indeed, I’m proud to have been able to learn first-hand what goes into processing shea for both the cosmetics and the food industries, and how this translates into jobs and income for Ghanaians.

Bunge Loders Croklaan has supported the U.S. government’s efforts in the shea industry for over a decade now, as a founding member of the Global Shea Alliance, and currently as a co-Vice President, representing suppliers on the Executive Committee – the governing body of the Alliance. Bunge has also been a strategic private sector partner, supporting the Sustainable Shea Initiative aimed at empowering rural women economically and socially, as well as the Action for Shea Parkland Initiative to promote, plant, and protect shea trees. Because the future of shea depends on the health and welfare of not just the women, youth, and the communities who are engaged in the sector but also the trees that provide this amazing crop.

Today’s visit demonstrates our collective efforts to advance the growth of the shea industry locally, and through these efforts to support the communities, and women and youth, whose incomes depend on them. Shea exports provide $33 million U.S. dollars annually to the incomes of women producers in Ghana. U.S. companies, like Bunge Loders Croklaan, alongside U.S. consumers, continue to play a key role in this growth, expanding U.S.-Ghana bilateral trade and investment, and ensuring that the shea industry continues to contribute to Ghana’s economic development, while meeting the highest social and sustainable environmental standards.

Thank you and medaase!

What Does It Take to Become an Ambassador?

]

]

On July 9, President Biden announced his intent to nominate a slate of appointments for some of the world’s most coveted positions. He proposed Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti as the United States ambassador to India, diplomat Denise Campbell Bauer as ambassador to the France and Monaco, career Foreign Service officer Peter D. Haas as ambassador to Bangladesh, and former Obama Foundation executive Bernadette M. Meehan as ambassador to Chile. Biden’s appointments have been anticipated by the diplomatic community for months, but as the appointments were announced, it raised the question, what does it mean to be named an ambassador?

Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti, who was picked by President Biden in July 2020 to be the United States Ambassador to India. Gary Coronado Getty Images

When Pamela Digby Churchill Harriman died in 1997, after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage during a swim in the pool at the Paris Ritz, an obituary in the New York Times called her “one of the most vivacious women on the international scene.”

At her funeral, held in Washington, D.C.’s National Cathedral, speakers included President Bill Clinton and Vice President Al Gore. Later, France’s then-president Jacques Chirac honored her with a posthumous Legion of Honor medal. Still, that Times obituary continued, “however great her accomplishments, [Harriman] could never put to rest the legend of the captivating woman who snared some of the world’s richest and most attractive men on two continents, marrying three of them.”

Pamela Harriman, at right, seen with Jackie Onassis and Averell Harriman, was the U.S. Ambassador to France under President Clinton. Images Press Getty Images

Indeed, Harriman—a British-born aristocrat turned Democratic fundraising powerhouse—who has been described as “the greatest courtesan of this century” had no diplomatic training. She was a poor student in her native England, described by some as what the English call “thick.” As an adult, however she found herself firmly installed at the intersection of society, power, and politics—dating Gianni Angelli and Edward R. Murrow; marrying Randolph Churchill, Leland Heyward, and W. Averill Harriman; palling around with Katharine Graham and Truman Capote. Harriman became a U.S. citizen in 1971 and went on to raise vast sums for Clinton—often through a political action committee nicknamed PamPAC—which was why her appointment as Ambassador to France in 1993 was not entirely surprising. In fact, she joined a venerable cadre of U.S. diplomats who had very little, in some cases no, experience in diplomacy when they received their posting.

Since the 1950s, presidents have consistently allocated roughly 30 percent of ambassadorial appointments to individuals who are not career diplomats—a practice known as patronage. Many of them have no background in international work at all, they’re simply rich and willing to open their wallets.

Harriman with Clinton at her Georgetown home in August 1992. WILFREDO LEE Getty Images

France is the oldest U.S. ally, and relations stretched back 225 years. It was a gamble putting Harriman, a former lover of Gianni Agnelli and Stavros Niarchos among others, in the position of being the highest-ranking envoy to the country. She was renowned for her parties and art collection, but not interest in trade relations. “Mrs. Harriman will never be seen as a great figure in the world of diplomacy,” Maureen Dowd wrote after Harriman’s death. “But she will be seen as a great figure in the world of salons—present at virtually every important juncture in the history of her time.”

Most of Harriman’s time at the Embassy on Avenue Gabriel—a sprawling building near Place de la Concorde where an annual July 4th celebration is one of the most coveted invitations in France—was spent hosting parties. She left the hard work of diplomacy to a respected State Department advisor, Avis Bohlen. Ambassadors always have staff, but Harriman, being a diva, became a slave-driver to her number two—probably not the only ambassador to do so.

Robert Wood Johnson IV, the New York Jets co-owner who served as President Trump’s ambassador to the Court of St. James. WPA Pool Getty Images

Yet despite the concerns when Harriman moved in and started re-decorating, she won over some observers—and not everyone shared Dowd’s opinion. “She made herself the most successful American political ambassador of the decade,” William Pfaff wrote in the International Herald Tribune.” During her time, the Dayton Peace Accords, which ended the bloody war in Bosnia, were signed in 1995. Richard Holbrooke, the legendary diplomat who served as U.S. Ambassador to Germany and the United Nations, was one of her fans. So was the French intellectual Bernard-Henri Lévy.

The Trump administration awarded more than 40 percent of appointments to individuals who were supporters but not foreign service officers. Robert Wood Johnson IV, heir to the Johnson and Johnson fortune and co-owner of the New York Jets, got the coveted Court of St. James in England; Carla Sands, a chiropractor, was named Ambassador to Denmark; David Friedman, a bankruptcy lawyer who represented Trump, snagged Ambassador to Israel, a crucial post; the handbag designer Lana Marks was dispatched as Ambassador to South Africa; Callista Gingrich, the author wife of Newt—a jet-set plus-one who New York said had “the cushiest gig in Europe”—was the Ambassador to the Holy See.

Trump used the political appointees more than many presidents, but one of the most disputed appointments in recent memory took place during the Obama administration. Colleen Bradley Bell, best known for producing the soap opera The Bold and the Beautiful, was appointed Ambassador to Hungary. The Washington Post said Bell came to “symbolize the problems with giving plum overseas diplomatic assignments to big political donors.” Ouch.

The late diplomat Richard Holbrooke, seen here with President Obama and Hillary Clinton in 2009, held positions including U.S. Ambassador to Germany and U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. SAUL LOEB Getty Images

Her strongest critic was the late Senator John McCain who gutted Bell’s lack of diplomatic experience and basic knowledge of Hungary, and pointed out that she had contributed $800,000 to Obama and bundled more than $2.1 million for his re-election.

“We’re about to vote on a totally unqualified individual to be ambassador to a nation which is very important to our national security interest,” McCain said during her hearings. “I am not against political appointees… I understand how the game is played, but… I urge my colleagues to put a stop to this foolishness.” James Bruno, a respected diplomat, later wrote that Bell, “could not answer questions about the United States’ strategic interests in Hungary.” None of this mattered. Bell went blithely to Budapest.

“I have always thought the American system of rewarding embassies to big donors has a lot of weakness to it especially when compared to other countries,” Jim Bittermann, CNN’s Senior Correspondent based in Paris, says, “Something I have said repeatedly is that one of the better investments in America [would be to donate] $200,000 to each of the two presidential candidates” You’d lose one of the wagers, he explains, but would probably be named ambassador to a medium-sized country.

A July 4th celebration at the American Embassy in Paris, where Pamela Harriman worked, lived, and entertained during her tenure. Bertrand Rindoff Petroff Getty Images

Ambassadors in these coveted positions get a salary, which pays back their wager, along with staff and cocktail parties for four years “if you play your cards right,” Bittermann adds. “And who knows what that Ambassador title might be worth thereafter.” Board positions, think tank positions, and consultancies are among the usual spoils.

Bittermann is not entirely against the system. He points out there have been appointees who did well in France: Felix Rohatyn, a former managing director of the investment bank Lazard Frères and the man credited with saving New York City from bankruptcy in the 1970s; as well as Craig Stapleton, a former owner of the Texas Rangers, and Charles Rivkin, an entertainment executive and current president of the Motion Picture Association. Each had their own skills and qualifications, none were career diplomats.

Across the English Channel, “the Court of St. James has always had attracted prominent businessmen and often significant donors to the election campaigns of those Presidents under whom they have served,” says the historian Christopher Silvester. “One would have to go back to Ray Seitz in the early 1990s to find an ambassador who had previously been a career diplomat and then back even further to 1976 to find another career diplomat in Anne Armstrong, the first and only woman to date who has been U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom, though she only lasted for a year.”

Joseph P. Kennedy with his wife and children in London during his stint as the American Ambassador to the United Kingdom. Keystone Getty Images

Silvester reels off a stream of former ambassadors: Armstrong’s successor, Kingman Brewster, had been president of Yale for over a decade, while Admiral William J. Crowe, who served under President Clinton in the mid-1990s, had previously been Chief of the General Staff under Presidents Reagan and George H.W. Bush. Elliot Richardson, a former U.S. Attorney General who stood up to President Nixon over Watergate, was Ambassador under Gerald Ford. “Before him there was a long string of rich businessmen, including Andrew Mellon, then Joseph P. Kennedy, Pamela Harriman’s last husband, Averell Harriman, and John Hay Whitney.”

Going further back in time, both Charles G. Dawes (1929-1931) and Frank B. Kellogg (1856-1937) were recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize (for separate reasons) and both of them had held high office back home, Kellogg as Secretary of States and Dawes as Vice President. Back in the 19th century both John Quincy Adams and Martin Van Buren had moved in the opposite direction, having served as Ministers Plenipotentiary to Great Britain (since in those days only monarchs or emperors sent ambassadors to London) before becoming U.S. Presidents.

Silvester sees no reason why the practice wouldn’t continue under President Biden. “If I were a career diplomat who played by the rules and abided bureaucracy,” he says, “it would be maddening.”

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io