Dhaka University: The nucleus of exploration of Bengali nationalism

]

]

Dhaka University officially began its journey on July 01, 1921. Unfortunately, the ongoing Corona crisis has hindered our ability to celebrate the birth centenary of our alma mater with the enthusiasm it deserves. At the same time, we are highly distressed over the fact that the birth centenary of the Father of the Nation could not be celebrated in a joyous atmosphere either. Moreover, we are not able to celebrate the golden jubilee of Bangladesh’s independence as we have been dreaming of. Thanks to the unprecedented development of digital technology following the visionary move of HPM Sheikh Hasina to achieve ‘Digital Bangladesh’, we can now observe these three ‘milestones’ at least ‘virtually’. Limited in-person programmes have also been planned and some already observed.

Undoubtedly, Dhaka University is the fountainhead of Bengali nationalism. In Bangabandhu’s own words, “My Bangla, my culture, my civilisation, my sky, my air, my history - these are the elements that make the nationalism of my Bangla. My Bangla’s struggle, my Bangla’s heritage, and blood create my Bengali nationalism.” (Speech in the Constituent Assembly on the draft constitution on October 12, 1972; see Dr. AH Khan’s ‘Selected Speech of Father of the Nation Bangabandhu, Ekattar Prakashani, 2011, p.97). The best practice of exploring our self-identity took place at the Dhaka University campus. Therefore, “Most of the important events of the freedom struggle of Bangladesh were organised in Dhaka University. And most of the heroes of this freedom struggle were students of this university.” (Rafiqul Islam, Dhaka University’s Contribution to the Freedom Struggle of Bangladesh, Dhaka University - Special supplement published on August 15, 1975, on the occasion of the arrival of Father of the Nation Bangabandhu, p. 81).

BRIEF HISTORY: After the partition of Bengal in 1905, a positive atmosphere developed in East Bengal, mainly for fulfilling the greater aspirations of the middle class, particularly the emerging Muslim middle class. However, after the annulment of the Partition of Bengal in 1911, the emerging middle class of the region was left with deep frustration and despair. In particular, the Muslim leadership led by Nawab Salimullah met the Viceroy Lord Hardinge during his visit to Dhaka in 1912 and put their demand for establishing Dhaka University to quell this anguish of the people of East Bengal. And the ball started rolling towards the creation of this university. Given this background, the unique role it has been playing ever since as the breeding ground for the renaissance of the people of this region cannot be denied.

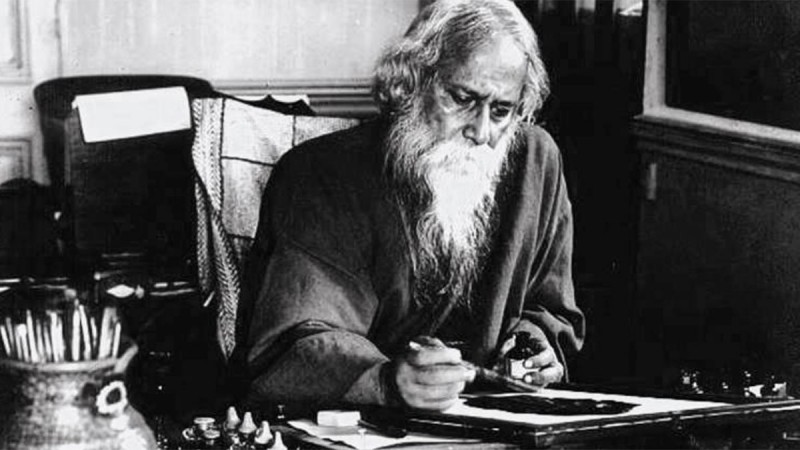

Alaknanda Patel, daughter of Professor Amiya Kumar Dasgupta, an early student of Dhaka University and a teacher in the Department of Economics, drew a touching image of Dhaka University after hearing about its heydays from her father, her father’s colleagues, and her own research. She quotes an autobiographical essay by her father’s friend Parimal Roy: “… Every evening, something is happening somewhere in the university - sometimes a debate, sometimes a drama, somewhere a seminar, somewhere a lecture. I used to think– what a grand arrangement, just for teaching us!” ((Patel, Alaknanda, ‘Prithibir Pathe Hente’, Bengal Publications, 2017, pp. 92). Undoubtedly, the period 1921-47 was the golden age of Dhaka University. Although many teachers left Dhaka after the partition, the University continued to follow the trend of attracting talented academics for many years to come. That the university could attract Rabindranath Tagore just within five years of its establishment who gave a couple of talks on contemporary socio-political and governance issues on February 10 and 13 in 1926 speaks a volume about its excellent moral strength and intellectual prows. This is the same University which had the reputation and ability to provide Doctor of Literature (D.Lit.) to personalities like Sir Abdur Rahim, Sir Jagodish Chandra Basu, Sir Prafulla Chandra Roy, Sir Jadunath Sarker, Sir Mohammad Iqbal, Rabindranath Tagore and Sarat Chandra Chatterjee, among others. No doubt, the teachers and students of this university protested government’s myopic decision of banning Tagore songs in the public media in early 1960s.

IN FREEDOM MOVEMENT: Besides contributing to excellent academic achievements, the teachers and students of this university were at the forefront of movements against the British colonial oppression, and later against the neo-colonial Pakistani ruling class. Soon after the establishment of Dhaka University, a significant section of the students pursued revolutionary activities for the liberation of their homeland. (Compiled and edited by Rangalal Sen et al. ‘Liberation War of Bangladesh: Contribution of Dhaka and Kolkata University’, UPL, 2018, p.15). Many students were associated with revolutionary Anil Roy and Leela Roy’s respective organisations ‘Sri-Sangha’ and ‘Deepali Sangha’. Many teachers also patronisd them. Moreover, Dhaka University was also the birthplace of the ‘Buddhir Mukti Andolan’ (Freedom of Intellect Movement). This tradition of free-thinking and pro-liberation intellectual activities had inspired the teachers and students of Dhaka University to join the subsequent democratic movements.

More significantly, the role of the teachers and students of Dhaka University in the language movement has been the brightest chapter in Bangladesh’s history. On September 15, 1947, Dhaka University-centric cultural organisation Tamuddun Majlish issued a pamphlet titled ‘Pakistaner Rashtra Bhasha: Bangla Na Urdu?’ (Pakistan’s State Language: Bengali or Urdu?) where the authors, Kazi Motahar Hossain, Abul Mansur Ahmed and Principal Abul Kashem made a strong case for introducing Bengali as one of the state languages of Pakistan. Meanwhile, an educational conference held in Karachi from November 27 to December 4, 1947, passed a resolution to make Urdu the lingua franca of Pakistan. The Dhaka University students and teachers marched towards the official residence of East Bengal Chief Minister Khwaja Nazimuddin in protest.

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, then law student of Dhaka University, emerged as a front-line leader from the very beginning of the language movement. On March 11, 1948, he was arrested along with some other student leaders when they were participating in the strike to observe the ‘Bangla Language Day’ programme. The detainees including Sheikh Mujib were released on March 15. Sheikh Mujib presided over the student meeting held on March 16 at Amtala. At a civic reception on March 21, Jinnah mentioned that Urdu would be the only state language of Pakistan. On March 24, he also mentioned the same at the special convocation speech at Carzon Hall in the university. The students immediately protested the announcement.

Meanwhile, Bangabandhu was arrested for taking a strong stand in favour of the class iv employees of Dhaka University. He was later expelled from the university as he refused to sign a bond pleading guilty. From 1949 to 1952, Sheikh Mujib was in jail for protesting the oppressive activities of the government. He was still in jail in 1952 when there were police shootings on the language movement activists. Even though he could not physically participate in the most explosive part of the language movement, he maintained communications with activists and leaders of the movement while receiving treatment from Dhaka Medical College hospital as an inmate. Consequently, he was transferred from the hospital to the central jail and later, to the Faridpur Jail where he began his planned hunger strike to push the demand of giving Bengali the status of a state language. Amidst such dire circumstances came February 21, 1952 and cemented its place in our history. Many people, including a few students of Dhaka University, were martyred that day, raising the stake of the language movement higher than ever before.

The influence of the language movement was well-felt in mainstream politics. We are aware of the outstanding role of Bangabandhu and his co-leaders, who had previously steered the language movement, behind the landslide victory of the United Front in the provincial elections of 1954. Unfortunately, the United Front government formed after that landslide victory was overthrown in just a few days by central intervention. Sheikh Mujib was the only minister in this government who had to go to jail. General Ayub Khan imposed Martial Law and declared himself President of Pakistan in October 1958. Sheikh Mujib was thrown into jail again.

In the sixties, Bangabandhu got out of jail and formed a powerful movement in favour of his proposed six points. Consequently, the Pakistani military junta imprisoned him again. During this period, students and teachers of Dhaka University formed a strong movement against the regional discrimination of Ayub’s regime. These students eventually incorporated Bangabandhu’s six points into their more intense eleven-point movement. As Bangabandhu was falsely accused and arrested in the Agartala conspiracy case, a mass uprising took place under the leadership of the students of Dhaka University demanding Mujib’s swift, unconditional release. After liberating Sheikh Mujib, the student leaders led by DUCSU Vice-President Tofael Ahmed conferred on him the title Bangabandhu.

The Ayub regime fell apart within a short period. Commander-in-chief of the army General Yahya Khan took over the power and promptly imposed martial law across the country. After much ado, he announced national elections. The students of Dhaka University actively participated in the election campaign and helped raise mass awareness in favour of the six-point programme given by Bangabandhu. In the election, the Awami League scored a historic victory. With this result, Bangabandhu achieved a remarkable moral victory as well. The Pakistani ruling class called the Constituent Assembly, only to postpone it abruptly. In protest, the non-cooperation movement began. Bangabandhu was the undisputed commander of that movement. On March 7, 1971, he essentially declared the independence of Bangladesh at the Ramna Racecourse maiden which is next to the university. In retaliation, the Pakistani rulers weaved a sinister, barbaric plan called ‘Operation Searchlight’. On March 25, 1971, the Pakistan military launched a vicious, unprovoked attack on the innocent people of Dhaka, brutally killing thousands of people overnight. In the face of a genocide, Bangabandhu formally declared the independence of Bangladesh in the early hours of March 26.

At Bangabandhu’s call, the students of Dhaka University jumped into the battlefield without hesitation. The teachers did not stay away either. Apart from India, they formed a public opinion in favour of the liberation war in the United Kingdom, the United States, and various countries in Europe. In a sense, the entire Mujibnagar government consisted of the alumni of Dhaka University. Their contribution to the war field is immeasurable. Many teachers, students, and staff of Dhaka University lost their lives on the horrific night of March 25. Everyone’s favorite Madhu Da was also killed in the carnage. Subsequently, many students of this university were martyred on the battlefield in 1971. Many lost limbs and bore the scars of the war for the rest of their lives. Breaking all conventions, the female students of Dhaka University directly participated in the liberation war, fighting on the frontlines. Many talented academics and intellectuals were martyred in a series of targeted attacks right before the end of the war when Bangladesh’s victory was imminent. Unfortunately, some teachers and students of Dhaka University joined the Pakistani aggressors and participated in the ruthless torturing and even killing of our dear teachers throughout the nine months of the war. This dark chapter will surely find a place in the history of Dhaka University.

AFTER INDEPENDENCE: In post-1971 Bangladesh, the teachers and students of Dhaka University continued to make remarkable contributions to the nation-building work. The Planning Commission formed soon after independence was headed by the teachers of Dhaka University. Almost all the secretaries were alumni of this university, so were most of the governors of Bangladesh Bank. Teachers and students of Dhaka University are still contributing significantly towards building Bangladesh. Most of the entrepreneurs who have played significant roles in Bangladesh’s economic development are also alumni of Dhaka University. Many a time, these prominent alumni have built large institutions of social development. These alumni are now providing important financial and moral support to the University of Dhaka through the Alumni Association. This trend needs to be further strengthened.

There is no denying that the quality of education in our university has fallen considerably compared to our glorious past. Our research funding is meagre. It is difficult for many students to pay for their education. Teachers lack the necessary incentives for doing research and publishing their works. Frustration about the low quality of education is prevalent at the national level. Covid-19 has further accentuated the crisis in our education sector. Its shadow must have fallen on Dhaka University as well. However, if our policymakers, academics, parents, students, and alumni want, it is possible to brighten up the outlook of the university so dear to our hearts. In our development journey, Dhaka University surely has all the potential to be the source of our national capability. With that optimism, let me congratulate all the teachers, students, employees, and alumni on this auspicious first day of the birth centenary of Dhaka University.

Dr Atiur Rahman is Bangabandhu Chair Professor at Dhaka University and a former Governor of Bangladesh Bank.

[email protected]

British Government had honoured Tagore with ‘Sir’, he returned the title after Jallianwala Bagh Scandal

]

]

Rabindranath Tagore earned a name in the whole world including India due to his writing. Rabindranath Tagore is also called ‘Gurudev’. He was a versatile person. He won Nobel Prize for his writing. The whole world is familiar with ‘Gurudev’ Rabindranath Tagore. Rabindranath Tagore was born on 7 May 1861 in Kolkata, the capital of West Bengal.

Rabindranath is known for many things, although the special thing is that Rabindranath is the first Indian to get the Nobel Prize. He is also the first non-European to receive this honour. In the year 1913, he was bestowed the Nobel Prize for Literature. Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize for his world-famous book ‘Geetanjali’. A total of 157 poems are included in this book. Rabindranath did not directly take the Nobel Prize. Rather this honour was taken by an ambassador of Britain on his behalf, then it was handed over to Rabindranath Tagore.

One of the special things related to Rabindranath is that he was honoured with the title of ‘Sir’ by the British government after being influenced by him. However, Tagore returned this title in the year 1919 after the Jallianwala Bagh scandal. The British government did not agree to take it, although Tagore, on the other hand, was adamant.

‘Gurudev’ Rabindranath Tagore wrote national anthem for two countries. The national anthem of India ‘Jan Gan Man’ and, the national anthem ‘Amar Shonar Bangla’, of Bangladesh.

Kangana retaliated on Aditya Thackeray’s statement, asked these 7 questions

Pakistan persecuting Minority Hindus for years

Corona outbreak in Israel, 1,721 new cases surfaced

How an Indian Religious Minority Shaped Modern Iran

]

]

TODAY, IRAN’S ZOROASTRIAN minority comprises a tiny proportion of the country’s overall population, considerably less than half a percent. The Zoroastrian community of India — where they are known as “Parsis” — is even tinier. But around a century ago, they became an object of fascination for a series of influential Iranian intellectuals, both Zoroastrian and Muslim, who repositioned their country’s pre-Islamic religion at the center of a new national identity. Coupled with the glories of the ancient Achaemenid Empire, this veneration for the Zoroastrian past won increasing state support during the half-century heyday of the Pahlavi monarchy before being pushed back into the margins of official culture by the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

Seen in the context of the other secular nationalisms that developed in the 20th-century Middle East, little seems unusual about the Iranian case. From Egypt to Lebanon, Turkey and even Afghanistan, pre-Muslim monuments such as the pyramids of Giza and the Buddhas of Bamiyan were by the 1930s being emblazoned on stamps and banknotes as evidence of both the deep roots of the nation and the prestige of inheriting an ancient civilization. But the Iranian case differed in one crucial way: whereas in Egypt no one had worshiped Osiris since the end of the Roman Empire, and Afghanistan hadn’t been home to Buddhists for more than a millennium, the sacred flames of Ahura Mazda quietly kept burning in a handful of fire temples in remote Zoroastrian villages skirting Iran’s central desert.

The old rituals had also been maintained by the long-separated Zoroastrian community of India. By taking advantage of the trading opportunities of Britain’s expanding empire, these Parsis (or “Persians”) had become some of the wealthiest citizens of Bombay (now Mumbai) during the century that saw it become the economic hub of the Indian Ocean. Looking across the seas through which their merchant ships traded as far as China, and across which their ancestors had sailed from the coasts of southern Iran, these wealthy Parsi businessmen made pledges to aid their impoverished coreligionists.

Renewing these connections was no small task. Over the course of 12 centuries in India, the Parsis had forgotten the spoken Persian of their forebears and now conversed in Gujarati or in English. But in 1854, after founding the Society for the Amelioration of the Condition of Zoroastrians in Persia, they dispatched from Bombay their educational and philanthropic representative, Manekji Limji Hataria. During the following decades, the tireless Manekji forged ties between the two tiny religious minorities that would transform the way in which millions of members of Iran’s majority Muslim community, including its ruling classes, conceived of their own identity.

When I first traveled to Iran in the 1990s to research the last traditional remnants of the old religion in the villages around Yazd, I had read about Manekji and the impact of his mission. But when I walked into the offices of the Anjoman (or community association) Manekji helped found in Tehran, running polite Persian phrases through my head, I was little prepared to be greeted in the impeccable English and Indian cadences of the mobed (or senior priest). Decades earlier, he had studied in Bombay as Manekji’s educational connections continued through the mid-20th century. But by the time I met them, the Zoroastrians were again in retreat, undertaking new migrations to California and Canada, and founding new Anjomans from Orange County to Ontario. Now, in Exile and the Nation, Afshin Marashi recounts the fascinating middle section of this story: the waxing and waning of modern Zoroastrianism as the links between two religious minorities in late colonial India and early Pahlavi Iran transformed the cultural politics of an entire country.

Through five chapter-long case studies of the most influential figures, both Zoroastrian and Muslim, who brought about this transformation, Marashi argues that these “intellectuals and nationalists came to imagine an Iranian modernity rooted in a rediscovered, reconceived, and reconstructed culture of Indo-Iranian classicism.” Here, as throughout his book, he presents the recovery of the Zoroastrian past as the romanticized promotion of a “classical” heritage for a modern nation-state whose secularizing leaders tried to replace their compatriots’ Muslim identity with a uniquely national culture that had the allure and legitimacy of antiquity.

In focusing mainly on scholars rather than politicians and ideologues, Marashi also uses “classicism” to hint at the intellectual methods that his Indian and Iranian protagonists shared with the European savants who taught some of them and whose own philological investigations into the Zoroastrian past had first emerged from the study of the Greco-Roman classics. Because the study of ancient languages — in this case the Avestan and Pahlavi Persian of the Zoroastrian scriptures — that laid the basis for this Indo-Iranian classicism emerged not only between Bombay and Tehran, but also involved the universities of Paris and particularly Berlin. By the 1930s, as this academic axis increasingly overlapped with its political counterpart, Bombay and Berlin acted as the competing transmission points for the rival ideologies of liberalism and nationalism. And so, through his meticulous and dispassionate investigations, Marashi documents how the recovery of the Zoroastrian past became ensnared in the political entanglements of the interwar age of extremes.

Each of the five core chapters follows the itinerant career of a key figure in this intellectual and ideological traffic between India, Iran, and Europe, a triangulation which lies at the heart of Marashi’s original approach to the lineage of Iranian nationalism that has too often been told as a two-way story of the Middle East and the West. Instead, he places Bombay — and its wealthy Zoroastrian Parsis — at the forefront of his history: they are the “exiles” who shape the “nation” in his book title. Or, rather, the Parsis are the exilic prime movers. For they draw to Bombay a sequence of subsequent exiles, or at least erstwhile émigrés, whose studies in India pave the way for the later sequence of studies in Paris and Berlin that imported to Iran a new awareness of a Zoroastrian past whose prestige was bolstered by the wealth of Parsi industrialists and the praise of German professors.

The first case study starts out in the early 1890s, when a provincial Iranian Zoroastrian called Arbab Kaykhosrow Shahrokh disembarked in Bombay for studies funded via the philanthropical ties initiated 40 years earlier by the port city’s wealthy Parsis. On returning home, Shahrokh brought with him the reformist approach to his religion which the Parsis had developed through their own interactions with Protestant Christian missionaries. As his studies in India also introduced him to Anglophone scholarship, Shahrokh’s subsequent writings — which included a Christian-inspired Zoroastrian catechism and a treatise on liberal theology — drew on the ideas of European and American “philo-Zoroastrians,” who romanticized Zoroaster as a blend of mage, mystic, and monotheist. During the more than three decades Shahrokh subsequently spent as president of the Tehran Anjoman, his career as a community leader in the capital city saw him improve the legal and social position of his fellow believers. Through what Marashi considers nothing less than his “reinvention” of Zoroastrianism, Shahrokh also raised the status of the religion in the eyes of Iranian Muslims, who, as a result of the cultural policies of the Pahlavi dynasty, were starting to see Zoroaster as their own ancestral — and national — prophet.

None of this could have happened had it not been for the wider promotion of Iran’s pre-Islamic heritage through the archaeological and historiographical projects associated with the ascendant Pahlavi nationalist elite. But while the European input into these developments has long been recognized, Marashi highlights the importance of Indian scholars, particularly the Bombay-raised Parsi Dinshaw Irani. After taking a degree in Persian and English literature at the University of Bombay, Dinshaw began studying the Avestan and Pahlavi languages in which the Zoroastrian scriptures were written. Later, as a Parsi public intellectual, he put his philological skills to broader use by writing three popular books that placed Zoroastrianism at the heart of Iran’s ancient, and now national, heritage.

Published in Bombay with the support of a Parsi charitable foundation, Dinshaw’s books were

intended to promote new understandings of Zoroastrianism that would enable the local Zoroastrian community to gain a new modernist understanding of their faith, and to help promote a sympathetic understanding of the faith to audiences of non-Zoroastrians. Both of these goals were ultimately intended to elevate the social and cultural status of the faith in the eyes on non-Zoroastrian Iranians, to encourage an ecumenical and pluralistic dialogue between the Zoroastrian tradition and Iranian Shi’ism, and to bring Zoroastrianism more fully into the center of emerging debates surrounding Iran’s national identity.

By the early 1930s, even as prestigious a figure as Rabindranath Tagore, the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, was seduced by this new vision of a pre-Islamic past that linked Zoroastrianism with Hinduism. And here is one of the key tensions that Marashi explores with exactitude and sensitivity. The articles and speeches in which Tagore celebrated a shared “Indo-Iranian civilization” divorced both regions from their 13-century-old Islamic heritage by emphasizing the more ancient ties between Avestan Persian and Vedic Sanskrit, as though this offered linguistic proof for essentialist visions of a Zoroastrian Iran and a Hindu India. Through the publicity that surrounded Tagore’s high-profile, state-sponsored tour, his nationalist hosts went further still in this eliding of over a millennium of Muslim history. If in Iran this was arguably less dangerous in that Zoroastrians were still a tiny minority compared with Muslims, then in India the stakes were far higher insofar as Muslims were themselves a minority compared with Hindus.

Many contemporaries were alarmed by the political implications. Among them was Sir Muhammad Iqbal, Muslim India’s most distinguished literary luminary and counterpart to Tagore as philosopher-poet, who sent letters of protest to Iranian diplomats. This was altogether ironic insofar as Tagore had previously published strident criticisms of the rise of nationalism in other regions of Asia. But during a decade that saw avowed cosmopolitans become allies of nationalists, these contradictions are precisely what interest Marashi as he dissects his corpus of sources in the manner of an ideological anatomy lesson, laying bare the subtle capillaries linking apparently different lines of thought.

In subsequent chapters, he turns to two Iranian figures: the scholar Ebrahim Purdavud and the activist Saif Azad. Their transnational careers took them to Beirut, Kabul, Paris, Berlin, and, of course, Bombay. Once again, that Parsi-enabled hub of Indo-Iranian exchange provided the neo-Zoroastrian template for the Pahlavi vision of a specifically Iranian rather than more broadly Islamic revival. Language played a key role as both obstacle and enabler of this reconnection with the ancient past of a religious minority. The Zoroastrian scriptures had now to be made both available and intelligible to Iran’s majority population and presented as their heritage as Iranians. Stepping in to satisfy this pressing demand came the Muslim scholar Purdavud and his Parsi associates, who translated the scriptures from ancient Avestan into modern Farsi, then printed them in Bombay for export to Iran. The result was to transform the Gathas and Yasna from mysterious and traditionally memorized liturgical texts, known only to tiny numbers of consecrated priests, into mass-printed, public translations which were not merely now accessible to ordinary Iranian Muslims, but presented to them as their own patrimony.

Once again, there were unintended outcomes of this two-way process of the Parsi rediscovery of Iran and the Iranian rediscovery of Zoroastrianism. These especially emerged as a result of separating an “authentic” classical Zoroastrian past from 13 centuries of “inauthentic” Islamic cultural accretions. Because as Marashi explains, “in practice this meant that the nonclassical elements of Iran’s history — in particular the Arab and Turkish elements — were now defined as external ingredients that had been artificially grafted onto Iran’s cultural heritage.”

Here, as throughout his account, Marashi is alert to the inconsistencies that appeared as intellectuals and ideas moved between the distinct sociopolitical environments of Iran, India, and Germany. At the core of this tension lay the “implicit contradictions between the liberal goals of the Parsis and the more nationalist goals of many Iranians” during the interwar decades of the 1920s and 1930s. By drawing on source materials from across this networked geography of “exile and the nation,” the added value of this approach lies not only in linking modern Iranian history to ideas in Europe (particularly the Paris and Berlin circles of émigré intellectuals and students). It also lies in showing how Iran’s older ties to a “Persianate world,” in which India had played a central part for centuries, continued into the modern era of European imperialism and reactively assertive nationalism. In showing how new scholarly methods, mass audience books, and an alternative national identity were imported from Bombay, then adapted to Iran’s contrasting sociopolitical context in unforeseen ways, Exile and the Nation is as important a contribution to colonial Indian history as it is to understanding the origins of the modern Middle East.

Marashi concludes by noting how, after the Islamic Revolution of 1979, “the intellectual project of Pahlavi nationalism was ultimately swept away by yet newer configurations of culture, politics and ideology,” which pushed the “culture of Indo-Iranian neoclassicism” into another cycle of overseas exile. Yet once reawaked, the memory of a non-Muslim identity was never fully erased, even in Iran’s determinedly Islamic Republic. When I visited the remote Zoroastrian pilgrimage site of Chak Chak 20 years ago, my companions were Muslim art students who viewed the shrine with spellbound reverence.

As that generation has grown older, and the state-sponsored Islam that replaced Pahlavi neoclassicism has increasingly lost its appeal, the search for alternatives has quietly grown stronger. In his recent Iranian Metaphysicals, Alireza Doostdar showed how many Tehranis have turned to imported New Age alternatives to state Shi‘ism. Others have begun converting to Iran’s older minority faiths by way of the Bahá’í faith, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism. But all such conversions are illegal. And so, like its counterpart a century ago, this more recent revival of Iran’s ancient religion is again surrounded by political tensions of the kind that Afshin Marashi so deftly reveals.

¤

Nile Green holds the Ibn Khaldun Endowed Chair in World History at UCLA. He is the author of Global Islam: A Very Short Introduction and host of the podcast Akbar’s Chamber: Experts Talk Islam.